By Johanna Wassholm & Anna Sundelin

What do ‘Rucksack Russians’ in Finland and Jewish pedlars in the United States have in common? The question occurred to us when we came across Hasia Diner’s book Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way (2015), while working on a manuscript for an article on itinerant trade in 19th century Finland. We noticed that many topics in Diner’s book are strikingly similar to those that we had noted in our sources, primarily consisting of ethnographic material and newspapers.

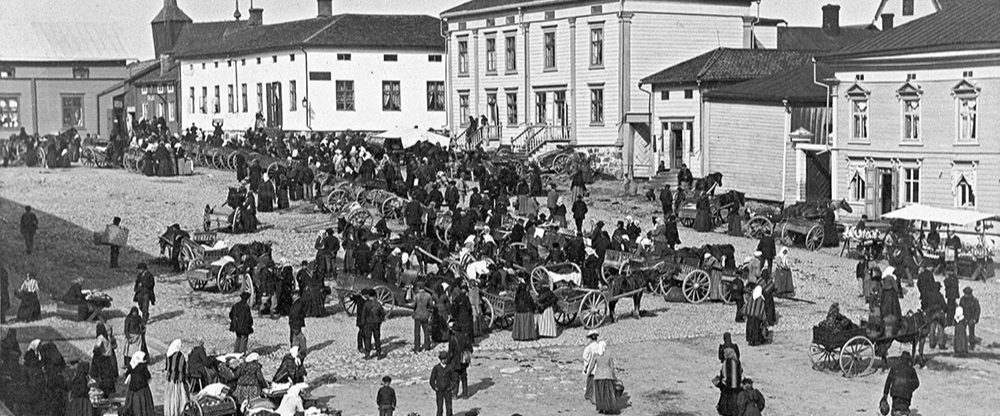

The ‘Rucksack Russians’ (Swe. laukku-ryss, arkangelit; Fin. laukku-ryssä), mostly men from Russian Carelia, engaged widely in itinerant trade in 19th century rural Finland. While Finland was incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1809, it was an autonomous Grand Duchy and its inhabitants had a separate citizenship right within the Empire. Thus, traders from Russia were treated as ‘foreigners’ in Finland, and their trade was formally illicit.

Our point of departure is that itinerant trade was not merely an economic phenomenon. As ethnologists pointed out in the 1980’s, the trade could also be studied from the perspective of cultural encounter. The ‘Rucksack Russians’ differed from their local customers in Finland through their Orthodox faith and some cultural attributes, such as language and clothing. At the same time, they played an important role in providing rural Finland with consumer goods. The late 19th century was a period of strong economic growth, which resulted in a constantly growing demand of new goods among the lower strata of society. The itinerant traders were received as regular visitors in many homes, often forming long-lasting relationships with the local communities, and sometimes settling down permanently.

Among the similarities we have found between the ‘Rucksack Russians’ and the Jewish pedlars in Diner’s book, we can mention but a few. Firstly, we share Diner’s view that the itinerant traders seem to have filled an obvious niche in the trading landscape. They provided specific groups of consumers with goods in a manner that other trade forms failed to do. We argue that the existence of this demand explains why the local communities, usually even the authorities, were unbothered by the fact that the ’Ruck-sack Russians’ engaged in an illicit trade. The profession was undoubtedly exhausting and unglamorous, and could even be perilous. Like the Jewish pedlars in the United States, ‘Ruck-sack Russians’ were occasionally robbed and even murdered. On the other hand, peddling was for many a temporary phase on the road to the middle class. Many pedlars did manage to save money and would later become successful shopkeepers.

Secondly, we agree with Diner, as well as with recent historians of consumption, that itinerant trade played an exceptionally important role for the consumption patterns of women. Women were the itinerant traders’ primary customer base, which our material also clearly illustrates. We see the peddlers’ trading practices as a form of ’spectacle’, which included an entertaining demonstration of the goods and haggling. This spectacle offered women an opportunity to practice trading and negotiating in their own household and in the absence of men. At the same time, the general suspicions directed against the traders often focused on the fear of them ‘seducing’ local women. These kinds of negative emotions were typically evoked when mobile people from the ‘outside’ were described as a threat to the local community. Despite the caution and a certain moral condemnation, romantic relations did form between the traders and local women. We have found numerous examples of relations between pedlars and local women that ended in marriage.

The article on the ‘Rucksack Russians’ forms part of the multidisciplinary research project Dealing with Difference; Peddlers, Consumers and Trading Encounters in Finland (Åbo Akademi University, 2017–2020). The project aims to broaden the understanding of the role that petty and itinerant trade played for the growing consumption of the lower strata of society and for cultural encounter in late 19th and early 20th century Finland. As the parallel between the ’Ruck-sack Russians’ in Finland and the Jewish pedlars in the United States illustrates, itinerant trade seems to have had similar functions and evoked similar emotions in different geopolitical settings. Thus, one major aim of our research project is to contribute to future comparative research on itinerant trade and cultural contact. Such comparative studies would further deepen the theoretical understandings of various aspects of mobile trans-national trade and retailer-consumer relations.

PhD Johanna Wassholm (johanna.wassholm@abo.fi) is a researcher in history at ÅAU. In the project, she studies the relationship between ethnicity and trade, with special focus on traders in Finland originating in the multi-ethnic Russian Empire (Russians, Carelians, Jews and Tatars).

PhD Anna Sundelin (anna.sundelin@abo.fi) is a researcher in history at ÅAU. Within this project, she studies the ‘Ruck-sack Russians’ and their trade, focusing on the traded goods and their use and meaning for the local customers in Finland.