On 19 November I was pleased to present at the symposium Imagining City Futures Across Disciplines, a Turku Institute of Advanced Studies (TIAS) event co-organized with SELMA, in cooperation with the Association for Literary Urban Studies.

The title of my paper was ‘Zoning versus Private Action: Envisaging Urban Futures in Twentieth-Century St Louis and Houston’. The point was to look at twentieth-century projections of the future and ask how this could become material for deepening our thinking on the futures of twenty-first cities. In terms of imaginative place, as proposed in Deep Locational Criticism, the effort in this specific case is to focus on regional intersections and not on a centre versus periphery model. The specifics of the Mississippi and Gulf Coast regions of the USA are vital here.

My study focused on specific planning texts of St Louis and Houston produced between the 1920s and the 1940s. It put these into dialogue with other views of the cities concerned. For St Louis, these would include the memoirs and poetic views of the city which I described in earlier presentations on it given this autumn (including those of T.S. Eliot, Henry Armstrong, and former residents of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex). For Houston, these included a 1940s guidebook to the city and the 1990s view of it given by the British novelist Alan Hollinghurst, who wrote of an approach to it as one along which cars:

career […] to the gathering rhythm of power pylons, used car lots, motels, the cacophony of billboards selling burgers, judges, vasectomy reversal, everything exposed and unashamed, the great aesthetic shock of America in all its barbarity and convenience (Hollinghurst, in GUST 1999 collection)

Cornerstones of the method include the study of city personality, the establishment of city typologies including those identifying specialized cities such as ports or leisure-focused cities, and the examination of text types not commonly thought literary, via techniques of literary analysis.

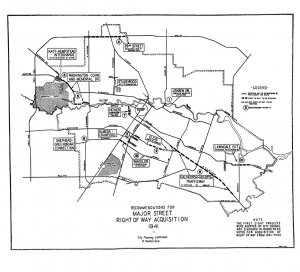

City plans are profoundly imaginative, even fictional, texts. St Louis, driven between 1915 and 1950 by the single-minded visions of Harland Bartholomew (1889-1989), differs profoundly from Houston, where official zoning was rejected in the 1920s and the general plan of the city that emerged in the 1940s was focused far more on facilitation than direction, above all through the improvement of the road network.

Image at top: from The Major Street plan for Houston and Vicinity (1942), public domain (archive.org).

My paper works with a long timescale of modern and migration. This begins half a century before Smith and Thomson produced Street Life in London when Italian political exiles began choosing the city as somewhere to live outside the reach of tyranny, and indeed reaching back to the turn of the nineteenth century heyday of the actor and comedian Joseph Grimaldi. The memory of this legendary clown was used to romanticize the area by a survival of the era of high modernism writing in the 1970s, Sacheverell Sitwell.

My paper works with a long timescale of modern and migration. This begins half a century before Smith and Thomson produced Street Life in London when Italian political exiles began choosing the city as somewhere to live outside the reach of tyranny, and indeed reaching back to the turn of the nineteenth century heyday of the actor and comedian Joseph Grimaldi. The memory of this legendary clown was used to romanticize the area by a survival of the era of high modernism writing in the 1970s, Sacheverell Sitwell.