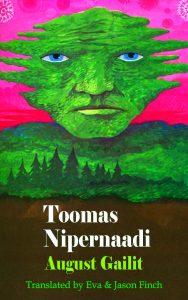

I published an article in the Spring 2019 Estonian Literary Magazine entitled “A Brief Guide to Toomas Nipernaadi’s Estonia”. It introduces the 2018 translation into English by Eva Finch and me of August Gailit’s 1928 novel Toomas Nipernaadi.

Here is the full text of the article, reproduced with permission from the Estonian Institute.

….

A Brief Guide to Toomas Nipernaadi’s Estonia

Jason Finch

The object of this guide is to supply curious readers, who are possibly also travellers in the country, with some information about the landscape and people of Estonia, in every way aiding them to derive enjoyment and instruction from a tour in this fascinating corner of Europe. The guide is founded on the travels through Estonia during one summer in the mid-1920s of a certain Toomas Nipernaadi, as recorded by August Gailit in his book named after Nipernaadi, first published in Estonian in 1928 and, in 2018, now translated into English for the first time (by Eva Finch and Jason Finch).

Actually, that introductory paragraph adapted from Baedeker’s Northern Italy (1906) might give a misleading impression. Toomas Nipernaadi, by August Gailit, is as every Estonian knows not a reliable travel guide but a work of fiction. It contains no map, and its place names are none of them found on a map apart from a few outside the boundaries of Estonia such as Riga and Sweden. It contains lush nature writing attentive to the flora and fauna of different parts of Estonia as the seasons subtly shift one into another. But it combines literary Romanticism with harshly entertaining satire on people and manners. Still, the idea of it as a guidebook to Estonia and Estonians, even if the reader has to fill in the blanks as to region or maakond, is a helpful way of seeing it. The book was written on a historical threshold, in the first decade of Estonian independence, and around the time when the country’s population began to be far more of an urban one and less of a rural one than it had ever been in earlier times.

But it is time to begin the tour. First we visit the Black River where the ice is breaking up at the end of winter.

All of the ditches, paths and hollows are full of gurgling rivulets jumping and wiggling like little worms, which rush merrily down the slope, turning into one thing in this charge, expanding and grabbing rotten leaves, twigs and moss and carrying all this on its back to the huge current of the river, a festive ballroom. The snow is brittle and glittery, it collapses in wind and sunshine, it ices over and drops of water tear off the ice crystals as from a dripping beard. The forest is waking from its wintry swaying, the tops of the spruces are getting greener and greener, and the broad boughs of pines are full of glistening droplets of water and birds chirruping. Autumnal sprigs, icy and red, have remained hanging on the naked rowans. Slopes and hills are shedding snowdrifts; brown cranberries and the frozen stems of lingonberries are lifting their heads as if from under a white sheepskin. The air is bluish, full of water and sun. (Toomas Nipernaadi, pp, 9–10)

Loki lives here, surrounded by forests. She shares a hut with her grumpy old father, Silver Kudisiim. Perhaps she is seventeen or so, perhaps a bit older. The neighbours are another father-daughter pair, old Habahannes and his daughter Mall. They seem ‘snooty and proud’ to Loki (p. 19). Much wealthier than she and her father are, they entertain the raftsmen who pass this year every spring as the weather changes, like now when ‘[t]he nights are warm and breezy, wetlands steaming and gurgling, waking up from their winter sleep’ (p. 13). This year, the raftsmen whizz past without stopping and Loki feels ‘unspeakably sorry for herself’ (p. 15). Days pass. But then another man arrives on a raft, all alone. He introduces himself to Kudisiim and Loki as Toomas Nipernaadi. Tales and trickery involving both the Habahanneses and the Kudisiims follow, in which it is sometime hard to tell who the trickster is and who is the one tricked.

Ultimately Toomas flees the region and his journey goes on as spring becomes summer. Six more tales follow. It’s a novel in short stories, according to the original title page. Every tale, or chapter, takes Toomas into a new region and a new phase of the year.

Having left Toomas leaping from a boat on the fast-flowing Black River and wading ashore, we meet him next on a ‘dusty road’ through a landscape which is not the ‘immeasurable forests’ surrounding Loki but one of lakes leading to a farm set in ‘dried-out fields’ (pp. 10, 39). Approaching Krootuse farm, we hear about Toomas, ‘tall and lean’ with ‘big eyes […] full of joy’.

When curious folk asked him something, he laughed with a wide mouth and told them that he was just wandering around looking for how the land really opened up. When he got tired he sat by the roadside, played the zither and sang, but his voice screeched and was ugly’ (p. 39).

At Krootuse, the Nõgikikas boys, Peetrus, Paulus and Joonatan, have just lost their mother Liis, by all accounts not a very nice person. Here, not for the last time, Toomas gets involved in a ceremony acting like a kind of pretend pastor: the funeral of Liis Nõgikikas, where he hands round a bottle of vodka he’s found in a cupboard, praising ‘the good qualities of the deceased’ (p. 44). As everywhere he goes, he becomes rapidly and deeply involved with the people he meets, country people with their own regions and localities who are still always very much country people: sometimes greedy, sometimes hungry for affection but always tied to the specifics of the area where they survive. Toomas comes into and out of their lives, a bit like a Baedeker tourist in the Italy of 1906, a traveller from ‘beyond forests and meadows’ (p. 44) except that he is in his own country and can always work charms with his speech in the language he shares with the people he meets.

Like Loki and her father, the Nõgikikas brothers are deep in a local rivalry. Theirs is with a pompous neighbouring farmer, Puuslik. Toomas offers help. He suggests they buy the apparatus needed to establish a travelling cinema including – the key thing to attract the crowds – a real live monkey. As he does in most places he goes, he courts a local girl, in this case the fisherman’s daughter Miila. As elsewhere, too, mayhem ensues, and Toomas moves on.

Instead of outlining the shenanigans which follow in different parts of Estonia as summer reaches its height then the days start getting shorter again and mellow September gives way to bitter October, this guide will now briefly outline the regions and landscapes visited by Toomas during the rest of this year. After the events at Krootuse farm, he is encountered next in ‘an upland area overlooking a valley’ where ‘[b]lue sea could be detected beyond the distant forests’ (p. 78). He reaches this idyllic setting is reached in late April or very early May, perhaps, the trees still ‘leafless’, ‘[t]he spring evening […] full of pollen and the scent of resin’.

By early June, as the longest days of the year are reached, he is in a great wetland, ‘the swamps and bogs of Maarla’ (p. 105). The nights now are ‘momentary, milky pale, blazing hit, full of a toxic fragrance’. The people around Maarla are said to be gypsies and horse thieves. They don’t have a good reputation among settled country folk. Here there is a ferry across a river which travellers pay to use. The former ferryman, ‘Lionhead’ Joona, fell madly in love with a gypsy girl and ended up taking both of them to their deaths over some rapids. Toomas presents himself as ‘a fen-drainer by profession’ (p, 124). When he applies his professional skills, he says, the area will utterly change. It will become a normal, law-abiding place, with money to be made there. As with the travelling cinema idea so at Maarla, Toomas presents himself to the locals as an incomer from a world of modernity and new technology which is implicitly the world of the town.

From Maarla we move to a Rabelaisian country wedding – where Toomas, briefly, officiates – in the village of Terikeste, on former manorial lands, an upland area of ‘clustered hillocks, ridges, wolds and hills with old oak trees, ashes and maples on the tops’ reached after ‘the Singa lowlands, forests and swamps run out’ (p. 175). And then after that Toomas enters another agricultural area where, in the ‘mildness’ of autumn, ‘the air is yellowish, saturated with the scents of earth, the aroma of the ripe grain and hops and the continuous quiet swish of the leaving birds’ (p. 241). The reader feels shades of change: Gailit is a splendid nature writer. Small alterations within something shared make the atmosphere different. Finally, beside the sea, the rain is becoming sleet then snow. It must be November. Toomas seems destitute, his boots worn out.

In every place there is a story. But as for Toomas’s own story, that only gets indicated to the reader at the very end of the book. Everywhere he goes he has been presenting himself as one thing or another: who is he really?

This isn’t a guide to August Gailit himself or to his literary circle. As all Estonians know, a road-movie called Nipernaadi was seen at the cinema in 1983 and afterwards many times on TV, but that belongs in another article.

Toomas Nipernaadi was written and is set at a time when Estonians were still primarily a rural people but when the old rural world was becoming a backward curiosity to the many city-dwellers now among their number. Gailit is more of a comic writer than England’s Thomas Hardy, but his portrait of the countryside has elegiac qualities, like Hardy’s. He shares with Hardy an intimate knowledge of how country people speak and judge one another. Gailit’s nature descriptions may resemble Wordsworth and Thoreau, but the crazy vigour of the book recall the trickster tales of African-American and Native-American literature. In Toomas Nipernaadi’s Estonia a set of elaborate pranks unfold against a rich landscape, ever-changing but ever-alike.

All page references are to August Gailit, Toomas Nipernaadi, trans. Eva Finch and Jason Finch (Sawtry, UK: Dedalus, 2018). ISBN: print, 9781910213506; ebook, 9781910213902.

Toomas Nipernaadi copyright © the estate of August Gailit 2018

Translation copyright © Eva Finch and Jason Finch 2018

My paper works with a long timescale of modern and migration. This begins half a century before Smith and Thomson produced Street Life in London when Italian political exiles began choosing the city as somewhere to live outside the reach of tyranny, and indeed reaching back to the turn of the nineteenth century heyday of the actor and comedian Joseph Grimaldi. The memory of this legendary clown was used to romanticize the area by a survival of the era of high modernism writing in the 1970s, Sacheverell Sitwell.

My paper works with a long timescale of modern and migration. This begins half a century before Smith and Thomson produced Street Life in London when Italian political exiles began choosing the city as somewhere to live outside the reach of tyranny, and indeed reaching back to the turn of the nineteenth century heyday of the actor and comedian Joseph Grimaldi. The memory of this legendary clown was used to romanticize the area by a survival of the era of high modernism writing in the 1970s, Sacheverell Sitwell.

that was green and bucolic. Some striking gardening. Picturesque variety among the types and sizes of smaller social housing blocks and individual terraced homes. The remaining taller blocks being overhauled; another up the hill towards some antennae standing alone in its non-clad form.

that was green and bucolic. Some striking gardening. Picturesque variety among the types and sizes of smaller social housing blocks and individual terraced homes. The remaining taller blocks being overhauled; another up the hill towards some antennae standing alone in its non-clad form. reet and the huge hole of works which now seems Birmingham’s centre. Never seen a city so remade. Up to the terrace in the library; finally back along pedestrianised streets with not a car or bus in sight. Pink trams crossed at Corporation Street / New Street junction, and a group of dancers entranced an audience, with a young man in black vest and loose pants twisting his arm around his head quite frighteningly.

reet and the huge hole of works which now seems Birmingham’s centre. Never seen a city so remade. Up to the terrace in the library; finally back along pedestrianised streets with not a car or bus in sight. Pink trams crossed at Corporation Street / New Street junction, and a group of dancers entranced an audience, with a young man in black vest and loose pants twisting his arm around his head quite frighteningly.

.

.

On 13 September 2018 I spoke at

On 13 September 2018 I spoke at  pate in such a dynamic event at this border city where several cultures meet. Apart from the formal discussions in the seminar room, a highlight was a guided tour of the now disused Kreenholm works (pictures from inside), a vast cotton mill with many ancillary buildings, on the western side of the Narva river separating the EU and Estonia from Russia to the east. Thanks go to the other organizers of the event, from the

pate in such a dynamic event at this border city where several cultures meet. Apart from the formal discussions in the seminar room, a highlight was a guided tour of the now disused Kreenholm works (pictures from inside), a vast cotton mill with many ancillary buildings, on the western side of the Narva river separating the EU and Estonia from Russia to the east. Thanks go to the other organizers of the event, from the