A while back, I came across this post about how science can make you feel stupid.

I shared it, thinking I understood perfectly what it meant and felt like. I actually didn’t then, because now I know what it means and feels like. (And yet, I am not exactly sure how it feels like. Stupid can take so many forms).

When I started off my PhD, I was like any normal person, motivated about starting a new “project” that they are excited about. It’s just like new year, and we all know how that goes:

1) You start off with a long list of resolutions;

2) You start following through on almost all of them immediately;

3) You feel so good that you are following through, and how this year did not turn out like last year (and we all know how that went);

4) You start realizing how by starting everything, you broke all rules of developing new habits, and how this is not sustainable at all (did you really even want all of this?);

5) You start going back to your normal routine, and your resolutions start feeling less important to you now;

6) New year, and you have almost forgotten (almost) how last year went and are ready for a new cycle of highly-motivated-to-back-to-“normal”.

But of course, everybody knows these stages, everyone has new-year moments. And when I started my PhD, I knew I’d face some kind of a slump some of the times. People-on-the-internet told me that the PhD dip is inevitable, and it is not a question of if you will come across it but when you will actually experience it (although they also told me that this phase comes sometime around the second year and I am still in my first, so am I just going through a trailer for the actual movie that will be officially opening in months to come?).

The thing is, despite knowing this, I didn’t really plan for this time (that is another kind of stupid right there). Because, like any normal person motivated about starting a new “project” that they are excited about, I wanted to be laser-focused on my PhD and on things that would take it forward.

So if I needed a break from lab work, I could read or catch up on literature, and if I needed a break from reading, I could take some online course. I did like doing other stuff, but all of that could wait until I had my PhD a little more on routine (a thing, that I am finding out only now, was not as easy as I supposed it was, but that could be for another time).

And this is the importance of comparatively-dumber-sounding other stuff.

Because when you are doing something as crazy as a PhD, where you can go months running around in circles finding your way back to square-one’s, feeling-stupid does become inevitable. And when you see it’s been a while since you last made progress, or learnt something new, or developed a new skill, or added something to you, yourself, as a person, that can be eexxttrreemmeellyy demotivating.

But other stuff can help you here.

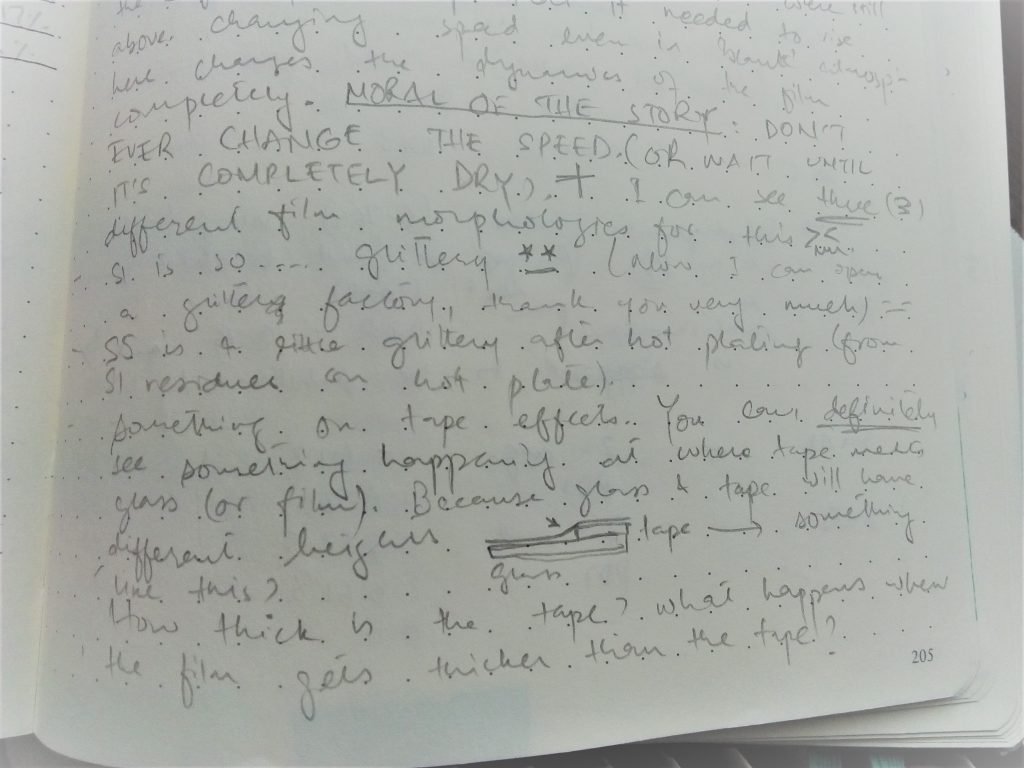

Because if you have a little something going on the side, like learning a new skill that may not be completely related to your PhD, it is some progress that you can, at least, show to yourself: So, yes, I still haven’t been able to decide if zinc chloride is better or if I should go for zinc acetate for my solutions, but I have completed six-hundred-and-eighty-five blog posts! That should be a milestone!

So that’s why I have started to think about starting other stuff this new semester. Like taking a language course (I have always wanted to learn another language and now might be a perfect opportunity), or starting to draw (I have some half-developed scripts for a comic on how my PhD stuff is going), or taking up other random workshops and activities where I can just change my environment and see what else is up in the world.

And there is another reason why the other stuff can be so complementary to your PhD: so now when you are moving about progress-less, you can blame it on the other stuff, and how, because of other stuff, you probably have not been able to focus on your PhD.

But the other stuff was your stupid idea, wasn’t it?