So this particular week in solar cells (some weeks ago), I finally managed to make my own batch of solar cells – after which I started to consider myself qualified enough – in the capacity of an independent solar cell researcher ^_^

Our Very Selfish Reasons

In one of our group meetings, a professor raised a very interesting question for us to think over: Why you are doing what you are doing and what is the importance of your work?

In research, this comes up a lot, especially when you are writing grants or research papers, or when you are presenting at conferences. At these times, you are expected to communicate the impact of your work and your motivation to get a doctoral degree (same stuff is supposed to work for both, pfft – after all, why would anyone be motivated to work on something if it wasn’t making an impact on the society and the world).

This time, when the question got popped all of a sudden, I was baffled.

I mean, I know why I am getting a PhD and why it is important (or at least I think I do). In fact, on better days, I have been known to drone on and on about why I am doing what I am doing. On regular days, however, I just trust that when we chose to enter this catastrophe, we had a very logical reason for it (even if we can’t remember it right now) and we were extremely passionate and excited about this new chapter.

Just as right now, when I am trying to pen it down in hopes that it’ll clear my own vision, I am completely clueless. But I do remember it was for some very selfish reason that I decided to take this path.

One of the reasons is probably that I want to continue in academia and nobody is going to let me in if I don’t have a PhD (a very self-centered point).

Of course, I would also like to have my own research group and students that I can squeeze scientists out of (I can only hope for the poor souls and myself).

Another (very selfish) reason that I can think of is the training that a PhD can offer. If I get through to the other side, I would expect myself to be quite good at doing some things, be more mentally tough, and to have grown considerably on personal and professional levels.

So I do think about this and I am completely aware that I should have a well-prepped answer for this for a time like when-a-professor-may-suddenly-throw-this-question-at-me. I should have a very good idea about the impact my work is making.

But on regular days, I don’t worry about it too much. I think that impact is over-rated for regular-day science. But then again, are we all not making an impact every day (positive or negative)? Don’t we all ruin or make someone’s day depending on how we interact with them? And when you are working interdisciplinarily, with all these other people, every little bit of science not only has an impact on your own work but also on the work of the people around you.

And more on a scientific level, wouldn’t I end up making some kind of impact anyway if I end up completing my degree? Even if I was planning on not making any? It may be very small, but it would have added something to the knowledge of the world.

But aside from all this glorious philosophical ranting, I do realize I need to have a well-prepared answer for difficult times (but then aren’t all humans selfish by nature and whatever we are doing, isn’t it all self-serving in some way?).

Right, yes, we need to focus on writing down a good response to this one that we can pull out of our hat in times of need (but then again…

The Light Bulb Moments

This is what science is made of: Long stretches of I-have-no-clue-what-this-means, but as you go along with it, you might find a light bulb or two (or more like, a couple burning candles)*.

Sometimes, you will go through literature and concepts which make no sense to you. You will go over them again and again without absorbing anything (like when you have to go over a sentence twice just to confirm that it is (indeed) written in English). Did you perhaps miss a lecture in your classes? Missed a lesson life might have been trying to teach you at some point in the past? Or are you just missing the point here? Were you just not made for this? Did that escalate really quickly**?.

You will feel hopeless and a failure and start debating every life decision you have made leading you to this particular research article. But, in time, you will find this is not entirely true. You will realize (at some point) that all that reading and going through concepts, again and again, was actually going through to your brain in some way. And that you are definitely not as dumb as you had started to think you were (not too many self-esteem points, though – you are still capable of dumbness, just not as much as you had begun to believe).

Somewhere along, you see that it has started to make some sense. That definitely this line that you are reading right now, this would have been complete nonsense a couple journal articles ago.

It doesn’t happen all of a sudden, not (at all) like someone has switched on a light bulb. But the vision slowly clears and you can see a little more. It’s like each new paper you go through, you start to understand everything just a bit better than before (in some kind of a cumulative effect).

That all that wandering wasn’t getting you lost. That there’s still hope for you (probably).

*This definition may differ from scientist to scientist.

**The answer is yes.

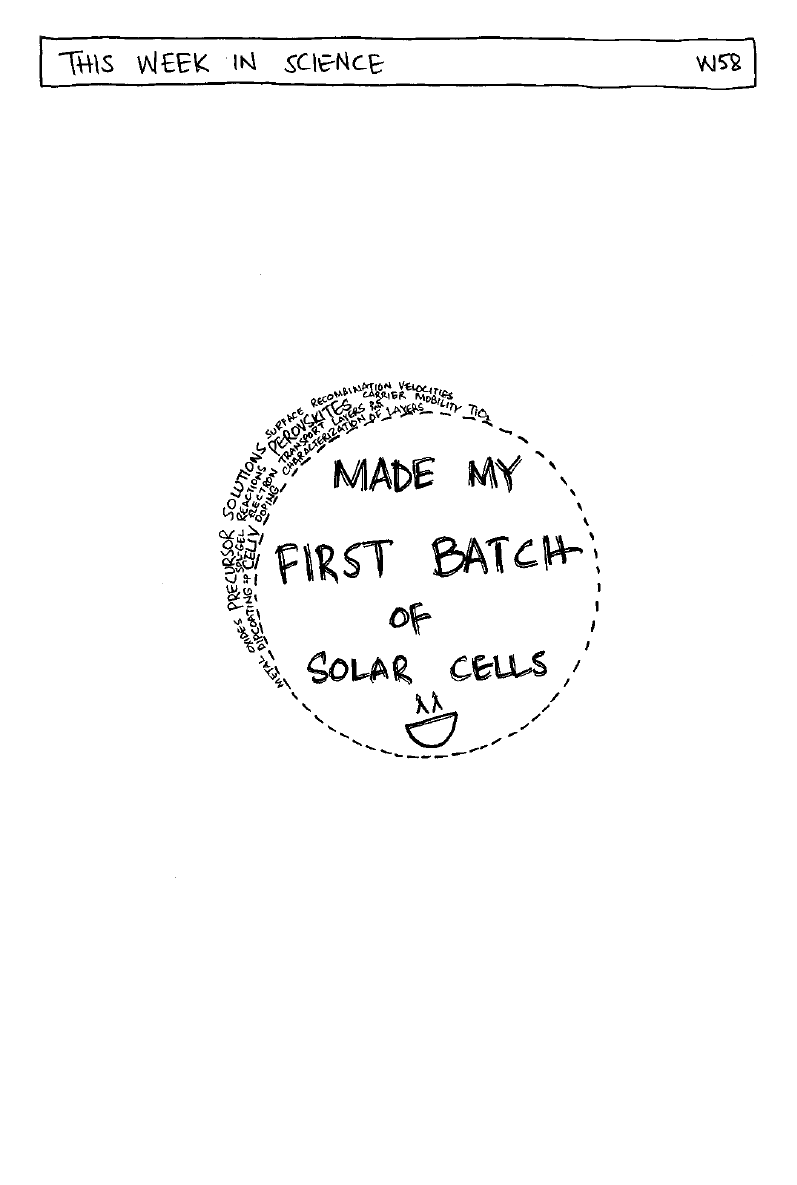

#2: This Week in Science: The Week of Didn’t Do’s

Mistakes That Follow You Around

Sometimes, things go wrong in your life that, no matter how much you try, you just cannot hide them.

Especially if you work with smelly chemicals in your lab.

You spill one of those and your biggest wish would be to bury the evidence of your clumsiness. It’s all well. You clean up, no big damages. No one saw you. It should be fine. Only if it was this simple.

The smell of the chemical will not let it be so. It haunts you and follows you around everywhere you go.

And people start asking questions. Questions that should not have been raised in the first place, that are best left unanswered.

And then, you have to admit that yes, it is you. This is something that you have done. And it is definitely you who smells like that chemical.

But in this adversity lies a masked opportunity. An opportunity to develop your own line of perfumes that smell like chemicals in your lab. Then you can wear them all the time and get the people in your lab accustomed to those smells.

So that next time, they won’t even know (plus you generate revenue. Win-win.)

The Finnish Happiness

When you are a foreigner exploring a new culture, there is no shortage of stuff to wonder about. Something will keep coming your way throughout your stay.

And so it has been many times when I (and my fellow foreigners) have wondered about Finland being the happiest country in the world, time and again.

This journey of discovery is to each their own. You can search it on the internet and easily find articles analyzing what the reasons are for it. But when you are living in Finland, that is just not enough, is it? You will notice your surroundings, think about this, discuss it with others, and try to find out why in the world is it so (because those articles on the internet, what do they know about it).

And in my personal journey-of-discovery, I think I may have come upon at least one profound, contributing factor.

Finland is basically a happy country. By default. In other parts of the world, people become happy if something happens, but in Finland, you can be happy if something doesn’t happen. Like slipping and falling on ice. This has to be one of the biggest factors. Like you went to work, walked the full some-150-meters distance of it, didn’t slip and fall down, and now you can be happy about it. In fact, now you can be happy about it everyday (seeing as the ice doesn’t seem to be going anywhere any time soon).

Tasks as mundane as getting groceries suddenly become feats of accomplishment (because, you guessed it, you didn’t slip and fall during the entire time you were out). And of course, this also gives rise to a sense of camaraderie with your fellow pedestrians, especially if you see someone slip a little and stumble. Then you can root for them to please-not-fall (and be happy for them when they have regained their balance).

Looking at it statistically, it is far more likely that you will have more days when you wouldn’t slip and fall compared to the few days when you, inevitably, will do. So more happy days. At least in this time of the year.

And if you can be happy in this slushy, icy time of the year, that should probably count.

Square Tomatoes

Some days ago, I found out about the square tomato.

In short, the “cultivar VF-145” was developed at UC Davis to get to a more sturdy kind of tomato that wouldn’t squish so easily and wouldn’t roll of conveyor belts. It is not really square, but just “less round” than a more round tomato.

Anyway, many different ways to look at, and solve, a single problem (and all the subsequent problems that arise because of that). Less manpower – Get in a machine to do it. The tomatoes roll off and get crushed by machines – Change the tomatoes.

Or perhaps it depends on the person you bring the problem to. Changing the tomato would probably be the first thing that comes to the mind of a plant breeder – but not necessarily to the mind of a solar cell researcher (not that solar cell researchers are the best people to solve tomato problems… It’s probably a good idea to leave them to tomato experts). But it does make one wonder: would the solution be still the same had someone else been on this task? Someone with a slightly different background and technical expertise?

I have had times in research when I was stumped by a mundane, and most of the times non-scientific, problem (which is, of course, mundane only in retrospect – no problem is too stupid, too mundane, or too small when it is in the phase of being a problem). I only had to move around, sometimes up and down some stairs, throwing the question at people I knew – and one of them would reply with an obvious solution that would leave you in a speechless why-didn’t-I-think-of-this state.

Times like these are when you find out who your real friends are – They are the ones who will not hesitate to break you out of your tunnel vision and bring you play-doh to seal your glassware airtight when you need it.

However, my biggest concern is completely unrelated to this now: Have I been eating square tomatoes all my life, thinking they were round when there were probably rounder tomatoes out there? Have I even seen a truly round tomato ever?

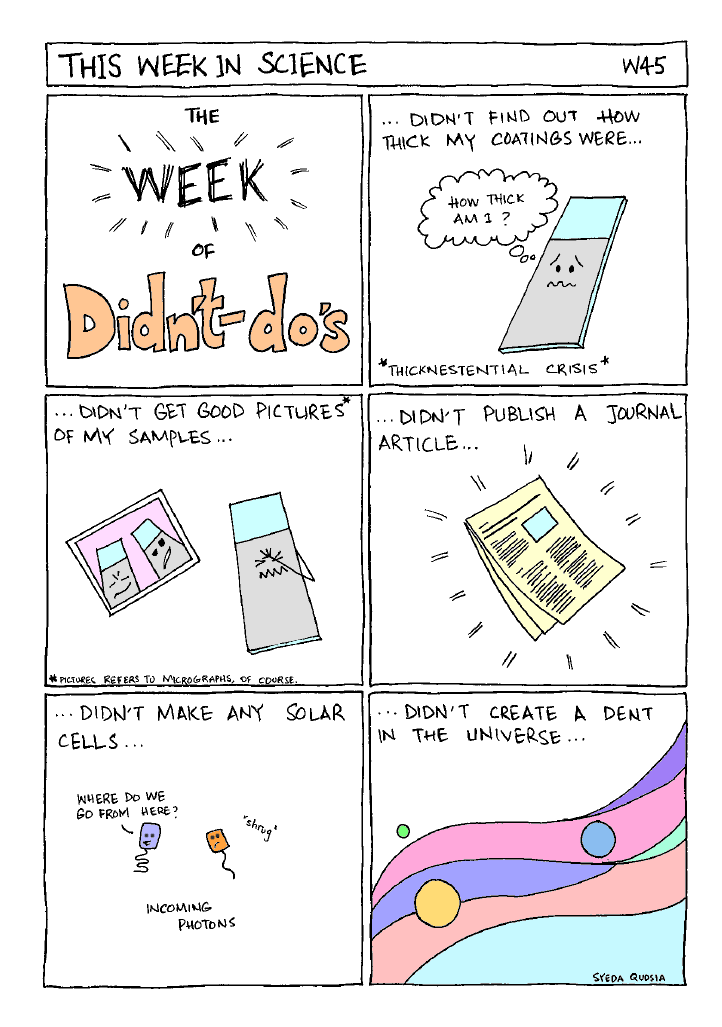

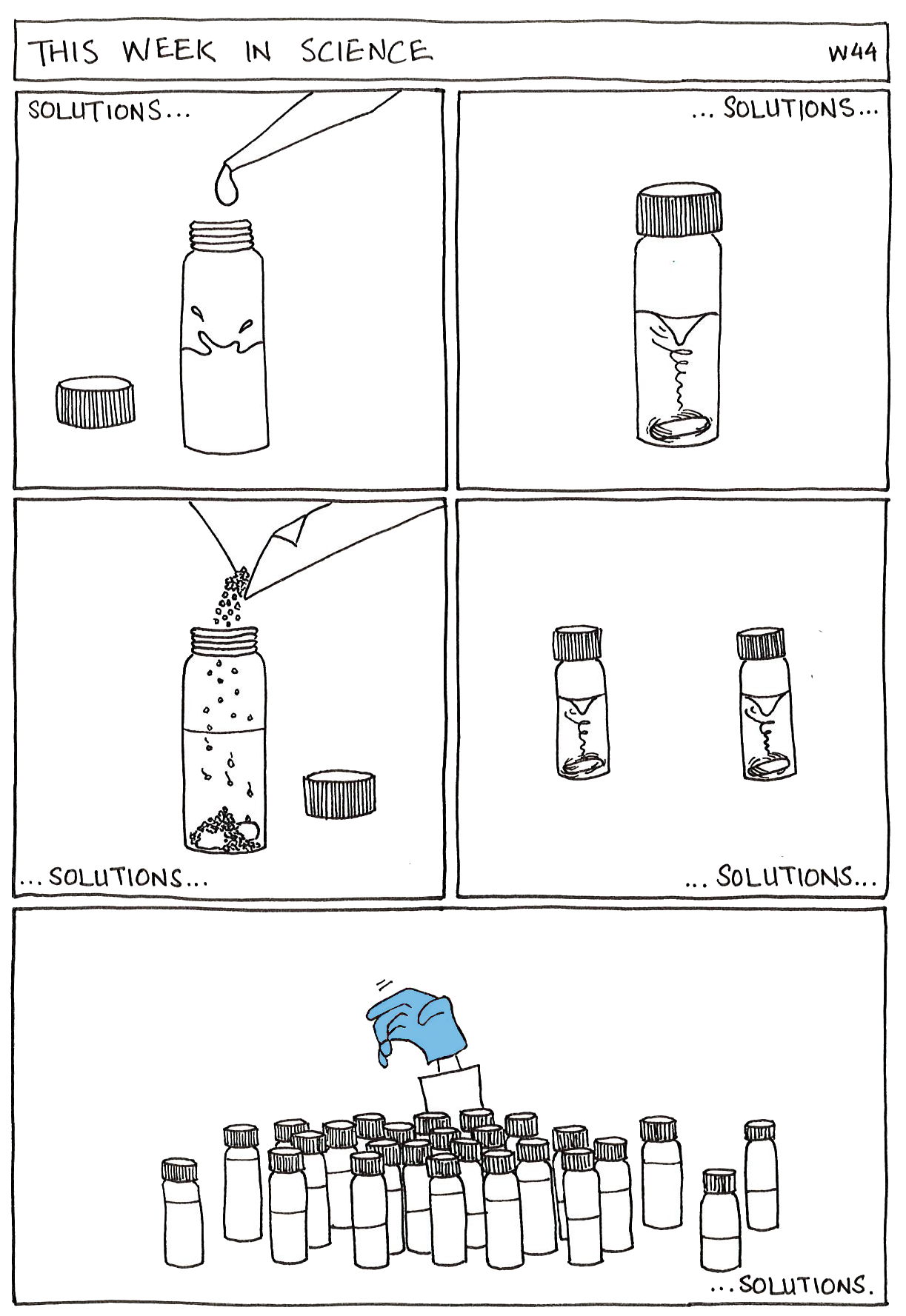

#1: This Week in Science…

Recently, my days in science have been quite eventful, and so I was inspired to render those into a short comic.

Pretty self-explanatory. Depicts my loss-of-words quite aptly.

Machine Learning

I would like to, first, apologize for the misleading title.

Wikipedia defines “machine learning” as:

Machine learning is a field of computer science that uses statistical techniques to give computer systems the ability to learn (e.g., progressively improve performance on a specific task) with data, without being explicitly programmed.

But that is not what this post is about.

You see, as a junior scientist about to embark on your career path, one thing you should do is learn to use different machines. Some machines will make something for you, whereas others will tell you that those machines are probably not working, and despite all your efforts, it will be some time before you start getting good samples or results out of any thing in your lab.

So if you work in a lab, you’ll now have a very good idea of who rules there: It’s them. Now and forward, in your time as a researcher, you’ll go into many labs, meet a lot of people, and learn a lot of new stuff… but nothing and no one will judge you like those silent machines sitting smugly atop work benches of your lab.

Many a times, I have started working with one, thinking, oh this is going to be one of the easier ones. Never has that attitude worked for me. It’s like you cannot trust any single one of them; even the ones that you think you know, won’t think twice when it is as tempting as shattering your trust in them.

They don’t care if you are enthusiastic about research and have chosen this field as your career with such joy. They will happily make you think that you have nice typical graphs* in your presentation that you are about to show in your group meeting. They want you to suffer, to taste embarrassment, like they want to see how long you are going to last in this field that you have been so passionate about …

… Until you have proven yourself worthy of research.

As a result, one of the few things I have always found myself doing in the beginning is to start gaining favor of the machines that are in my lab. To build good rapport with them. And it is not easy, not with every machine. Even after you feel you two are going along well, they will still test you, or just throw you under the bus when they feel like it**.

If it all sounds depressing to you, let me tell you there is hope. Somehow, after you have stood beside them long hours and worked with them at odd times***, they will start to slowly accept you and let you enter the ranks of researchers. It’s blood, sweat and tears to gain that kind of trust, but you can gain the status of meh-you’ll-do in the eyes of the machines.

But don’t ever expect them to start liking you, because that’s ridiculous, they probably don’t have a heart.

* Well, okay, they may have been looking a little weird to you as well, but early on, you wouldn’t know that, thinking this is probably how they are supposed to be.

** Which tends to happen most on Fridays, followed next in probability by Mondays.

*** Condition of high-levels-of-consistency needs to be met with these requirements of long-hours and odd-times.

Culture Shock (Again)

Wait, haven’t I written about this before?

Seems like I have… But l appear to have the phrase stuck in my head.

Never mind, I’m a changed person now, so anything I write today (on the same topic) cannot be the same as what I might have written four (and something) moons ago.

So I shall write on this again.

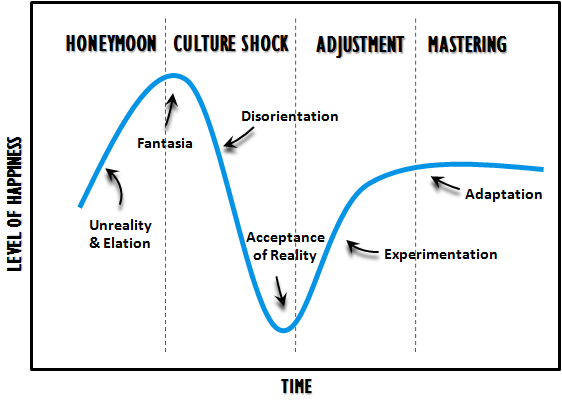

And today, now eight (and something) moons into my PhD, I expect myself to have grown somewhat in my scientific capabilities. So we shall talk about culture shock the scientific way, the “graph” way (excuse my English, but I am a foreigner, so I can apparently do whatever I feel like without feeling as bad about it).

And well, the graph-way is the right way, or it becomes so once you start falling in love with this kind of data representation, which is inevitable if you science (again, I am a foreigner, and “science” feels more like a verb to me these days).

But anyway, back to the graph:

Of course this is a very generalized curve, and just one “dip” in the experience is untrue for quite some people – this graph should be a lot more “noisy” if you’d plot a real one. Although this would differ from person to person, and how different of a culture you are moving into.

Also, the graph doesn’t really show your “mastery” level at your home country (or town). But from the text available on the internet, it is apparent that you almost never reach the same level of mastery in your new culture that you had in your old culture (which makes sense if you think about it).

This always makes me wonder… Does this mean that, even after you have adjusted and adapted, you are technically still in a state of culture shock, and will probably remain there throughout your stay?

That I find scary. And a little unrealistic to mention if a discussion about culture shock comes up in, say, two years from today. What do I do then? Do I say I am still in culture shock, if this particular question comes up? (Although I would estimate that to be a highly unlikely scenario, but everything has a first time, doesn’t it?)

But having grown comfortable with the idea of culture shock, and the (somewhat embarrassing) fact that I am still in there somewhere (although now probably in an overall better part of the curve), and being there for perhaps as long as I am in Finland, I have also realized the good this will do to my self-esteem…

So if I am not as good as I am hoping to become… heck, I am just in the wrong country!