It hadn’t been past 12 yesterday when I had officially declared it a bad day for science.

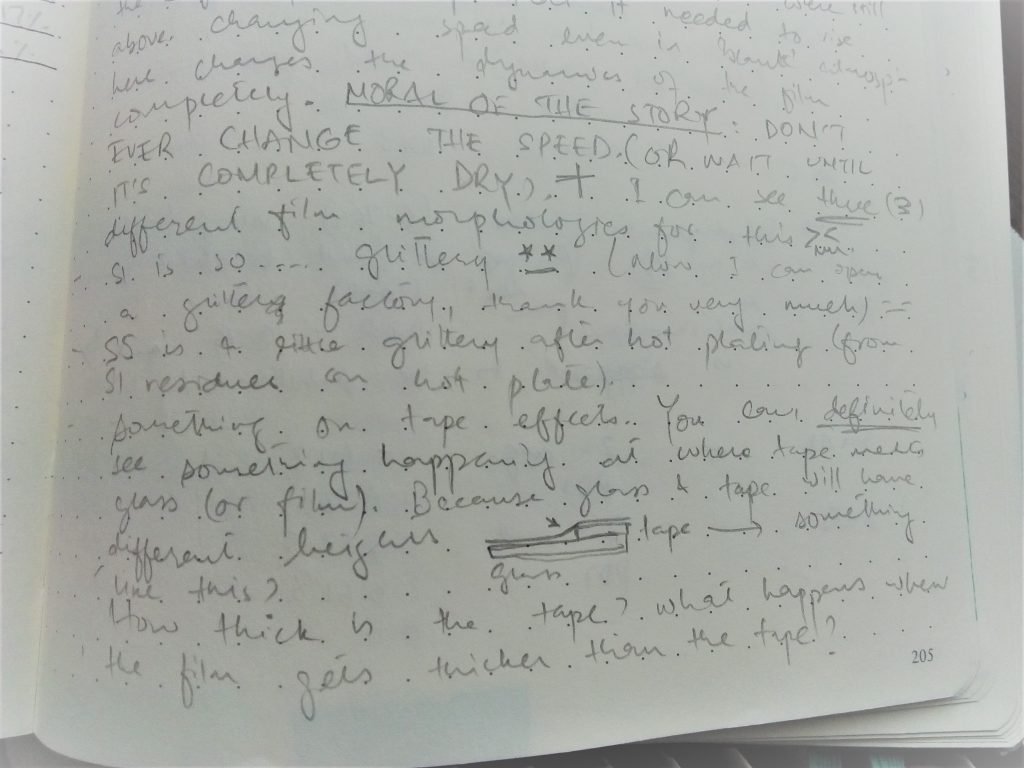

The hot plate I was supposed to be using extensively broke down (again!) and I discovered that one of the good things going on seemed so rosy because I had been miscalculating some things (and misleading myself and others about how it was going so good at that end).

Having been through all that by 11, well, what could happen now that would make it a better day?

But in retrospect, I think I may have labelled yesterday a little too soon – because the day itself didn’t turn out that bad after all.

We, scientists, we label. And that’s a good thing. You should label all your solutions and chemicals as soon as possible, even before you put your stuff in a blank bottle, but essentially ahead of forgetting what you put in there (and until you have labelled these, your life hangs in some kind of a science-purgatory where you keep chanting the words in your head until you have penned it down where it belongs).

But today – today when I was again tempted to categorize the day in the bad-days* section, I reminded myself that a scientist should not label her days as hastily as she should label her sample bottles.

* A “bad” day for science constitutes all days that are worse than your usual days, when it’s normal that things don’t always work the way you want them to. A “bad” day happens when you discover having an outlier compared to your average kind of day (which can normally be rated quite close to each other on a scale of 1 to 10).