Wait, haven’t I written about this before?

Seems like I have… But l appear to have the phrase stuck in my head.

Never mind, I’m a changed person now, so anything I write today (on the same topic) cannot be the same as what I might have written four (and something) moons ago.

So I shall write on this again.

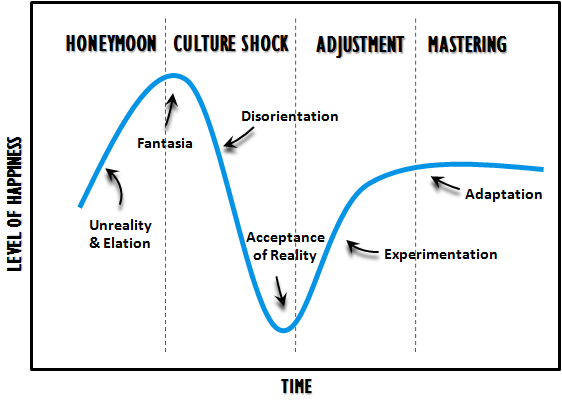

And today, now eight (and something) moons into my PhD, I expect myself to have grown somewhat in my scientific capabilities. So we shall talk about culture shock the scientific way, the “graph” way (excuse my English, but I am a foreigner, so I can apparently do whatever I feel like without feeling as bad about it).

And well, the graph-way is the right way, or it becomes so once you start falling in love with this kind of data representation, which is inevitable if you science (again, I am a foreigner, and “science” feels more like a verb to me these days).

But anyway, back to the graph:

Of course this is a very generalized curve, and just one “dip” in the experience is untrue for quite some people – this graph should be a lot more “noisy” if you’d plot a real one. Although this would differ from person to person, and how different of a culture you are moving into.

Also, the graph doesn’t really show your “mastery” level at your home country (or town). But from the text available on the internet, it is apparent that you almost never reach the same level of mastery in your new culture that you had in your old culture (which makes sense if you think about it).

This always makes me wonder… Does this mean that, even after you have adjusted and adapted, you are technically still in a state of culture shock, and will probably remain there throughout your stay?

That I find scary. And a little unrealistic to mention if a discussion about culture shock comes up in, say, two years from today. What do I do then? Do I say I am still in culture shock, if this particular question comes up? (Although I would estimate that to be a highly unlikely scenario, but everything has a first time, doesn’t it?)

But having grown comfortable with the idea of culture shock, and the (somewhat embarrassing) fact that I am still in there somewhere (although now probably in an overall better part of the curve), and being there for perhaps as long as I am in Finland, I have also realized the good this will do to my self-esteem…

So if I am not as good as I am hoping to become… heck, I am just in the wrong country!