It’s a very good thing to practice optimism in life. Optimism can keep you going in the face of challenges, and absurd optimism can keep you going despite past failed experiences and your knowledge of all odds being against you.

But in general, optimism is healthy, and I have been thinking about practicing more of this optimistic approach to life in general.

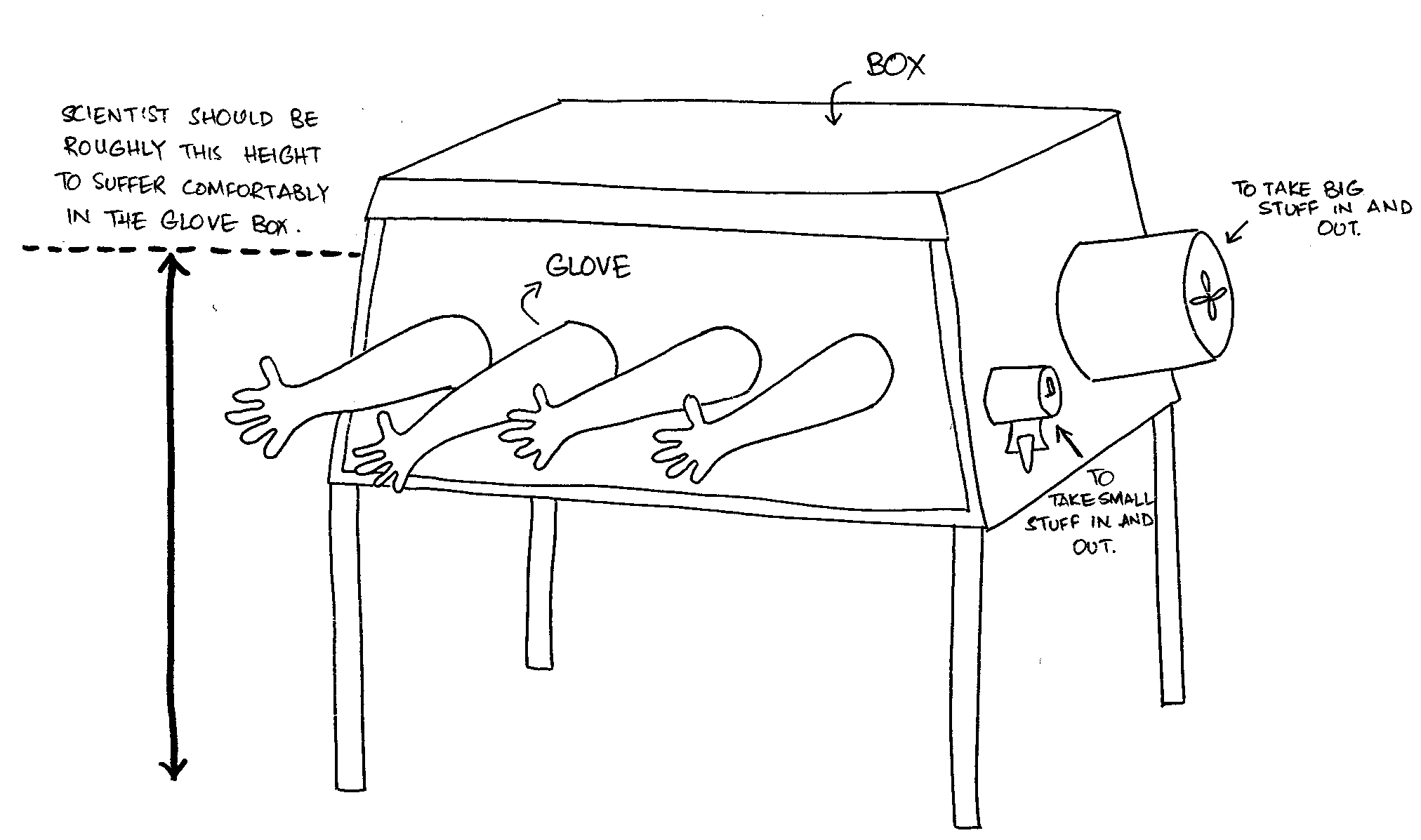

Except when it comes to my lab work. There, I don’t see how optimism helps me.

Because lab work, well, you can never be too sure about lab work.

And, as past experiments have shown, 95% of experiments don’t usually work the way you want them to (and if you are optimizing some procedure or recipe, the success rate can be quite close to zero).

In principle, I could be optimistic about my experiments before I start them, that may be this is THE time they will work.

But being a scientist, how can you just ignore the evidence of your low success rate of past experiments? How can you disregard all that data?

The thing is, it is easy to be optimistic and hard to be a realistic pessimist. It’s also called “the planning fallacy”, which describes how we, humans, are optimistic about our abilities and predict we can do things much faster and smarter than we actually are able to.

And I have been subject to this planning fallacy numerous times. Dozens of times I have thought I could do my part in group assignments well in time, or that I could surely submit a work update to my supervisor by the end of a week. Or that by July, I’d surely be at a stage where I’d be making my own Perovskite solar cell devices (didn’t happen, just so you know).

90% of the times, though, I have found myself not even close to meeting those deadlines.

So with the lab work, I have no choice but to opt for pessimism as my approach-of-choice to go about it. That despite every strategy that I develop to get my next solution not-cloudy, is probably not going to work, because:

1) It didn’t work the last time, when I very well thought that may be this in THE time it will work.

2) If it, by some tiny amount of chance, does work, and the cloudiness from my solutions clear up, well then, that is exactly how I’d prefer it, wouldn’t I?

So, in the long run, pessimism in the lab is a better option. If it doesn’t work, you are not disappointed, because you knew it wouldn’t work.

And if it does work, you can be twice more happy compared to if you thought that may be this in THE time it will work.

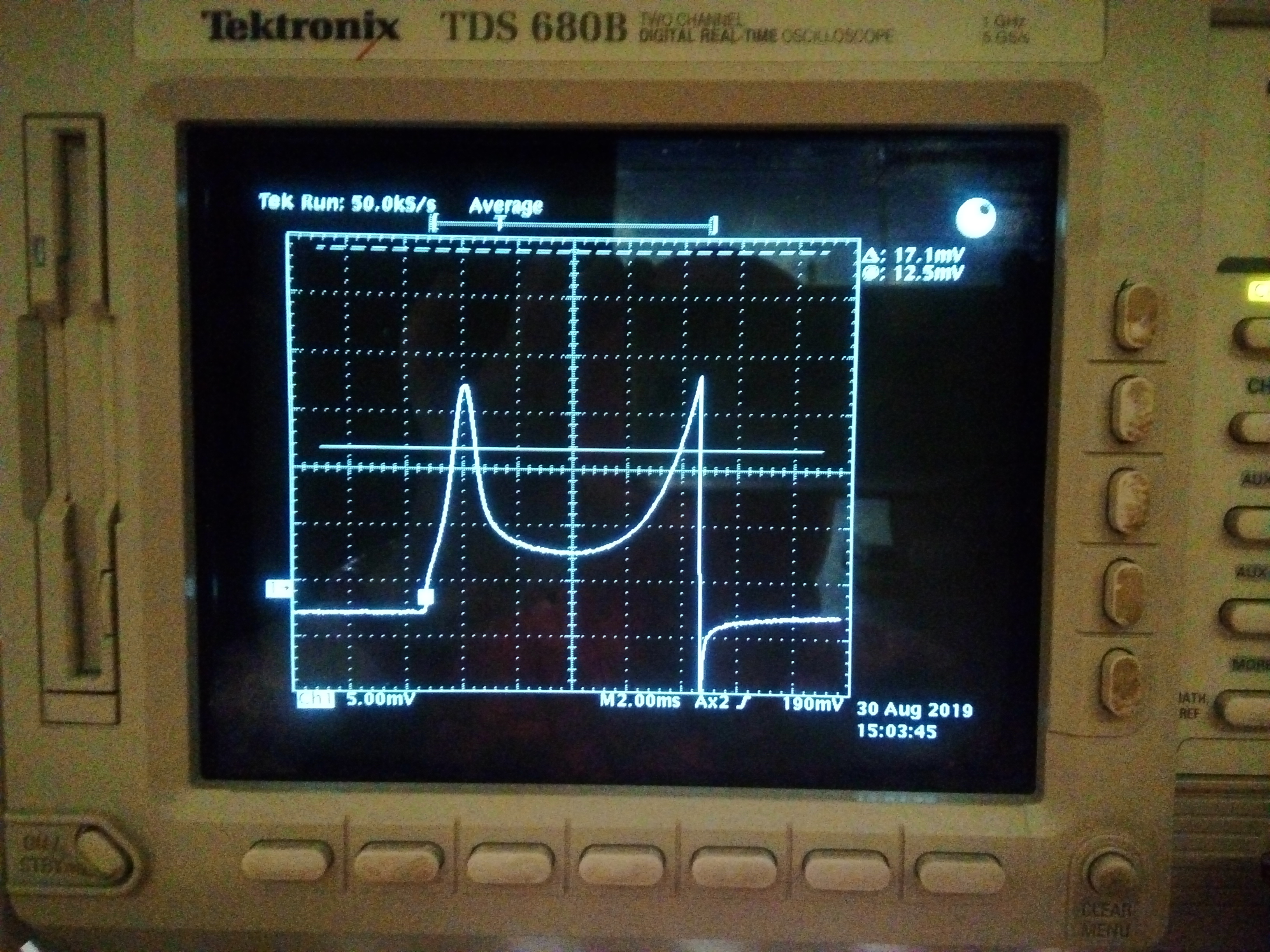

P. S. However, of course, there is a catch. If all of a sudden, everything starts going right in the lab, well, that’s enough ground to include skepticism in your mix of pessimism.