Some background information first: I am a foreigner in Finland.

It happens so, from time to time, that when people from my home country are considering a PhD abroad, particularly in Finland, and they somehow know me (directly or through mutual friends), we get into conversations about the pros and cons, the good and bad stuff, the easy and tough parts.

One of the FAQs include the language question.

In my two years here, I have not yet come up with a good short answer. Is there a language barrier in Finland? No, but yes there is. Or more like, yes, but apparently not.

I find this to be one of the weird things about my whole experience, and I never imagined that the “language barrier” would play out quite like this.

Back when I was on the other side, and I was gathering information on different aspects of adjustment, and asking people and disentangling information from the internet webs, I was told that English is fine! Almost everybody speaks English and there are no problems. They are, of course, right.

Ask me and I will tell you that of course you can survive and move about fine with just knowing English. Heck, I have myself done it for almost two years now. But I will also tell you that despite this, there is, in fact, a language barrier in Finland. And because of this, the existing language barrier is never acknowledged. I will also tell you to not take this too seriously and this is probably kind of fine-print information (not to mention, everyone has different experiences and what might feel like an ocean to me could be just a drop in the bucket for other people).

Now, I have come to realize that my methods of adjustments rely heavily on the language. In a new place, it helps to know your boundaries and how much you can dive in appropriately. And, being potentially awkward questions to ask directly, how does one get this kind of information otherwise? By observing one’s environment and noticing the interactions between already-established people in the “culture” (read: by overhearing conversations).

That ways you know if you should just keep it work-related, or if you could joke around a little bit and share light-hearted, other-workly information. And as you put together your own big picture, you see where you can and cannot fit in, in what aspects will you be limited yourself, and if you can establish a state of equilibrium with your environment.

In case there’s a “language barrier”, you are cut-off from this very important source of information. And in case of Finland, where, as the internet says, people don’t talk, or don’t like to talk, or whatever it is actually that they have with the act of talking, this effect is magnified.

So when they are talking among themselves, what is it really that they are talking about? Just work, probably? Or that’s how you start off, more or less.

Now, in my two years of observing and speculating and trying to put together the pieces of my yet-incomplete puzzle, I have reached the conclusion that the Finns do talk, at least, but they are probably not always talking about work. Though still not sure how much. Also not sure if they have a gossip culture and office politics. Also not sure how much is appropriate and how much isn’t. To some extent, I can tell which people in my environment are more friendly and which are not as friendly with each other, but I cannot say how much friendly those people are with each other.

So, yes, there’s a language barrier in Finland that nobody is ready to acknowledge because, of course, everybody speaks English, and what needs to be communicated is being communicated. Survival prospects of internationals are actually pretty nice, even if they are not up for learning the language.

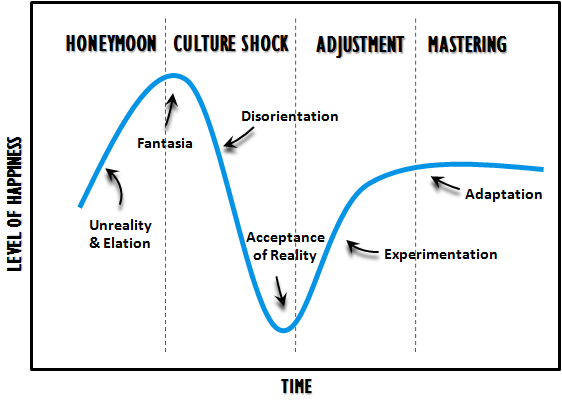

Another way that this language barrier is amplified is when you are sitting in a group and the already-established people just kind of forget you are there and start conversing in their local language. The feelings of exclusion can be tremendous and these can be the main moments where you truly experience a “culture shock”. Still, I assume this is relative to what culture you are coming from and what your host culture is. I expect that in more social and inclusive host cultures, this might not hit a new person so hard (if they feel included in other aspects in their environment).

(Older posts on culture shock: here and here).

There’s only one way I have found around this, so far: Learning the language, irrespective of if you are good with communicating in English only, and even if you are not planning to speak in your new language. Having now taken two Swedish courses, I can tell at least when they are talking in Swedish vs. Finnish. Also, recently I realized that while I can still not understand what the already-established people say while talking among themselves, I can finally get the gist of what is being talked about.

Most importantly, if you are in a gathering and they forget you and start talking among themselves, it at least becomes interesting to try and understand what they are talking about, or you can just imagine it as your usual Swedish listening practice.