Okay, you don’t have to do much; write one sentence and we’ll consider it a win.

Trylingualism

So you are in this foreign country now. And you have been learning a new language for some time.

One day, in the streets, you pass some street sign and, woah, you could understand (some of) it!

After some time, it becomes quite common – that you look at some written words and you totally understand what they mean. Piece of cake, so easy. So easy that you don’t even notice it anymore.

On another particular day, you pass a sign and you understand it, as usual. But THEN, you realize that that sign was NOT in the language you were learning. You were not supposed to understand this one. Oh no!

This was the big question about learning a language in Finland. The main language is, of course, Finnish. But then Finland has a Swedish-speaking minority and the university that I was going to was the Swedish-Speaking University of Finland. So which one to learn? Swedish or Finnish? (Well, the answer to that was: Both!). Or rather, which one to learn first? Finnish or Swedish?

Back when I was coming to Finland, I had already started doing Finnish vocabulary, but once here, I decided to opt for Swedish. Swedish was easier to learn (so said the internet) and I could see an end point for it. Not to mention, the people in my more immediate surroundings were Swedish-speakers.

So this is how the equation set in my mind at that time: If I would start Finnish and it would take me two years, I might still not be good enough, making it unfavorable to start Swedish. But if I start Swedish, which was easier to do, there was a bigger possibility that I might reach a stage where I could then jump to Finnish, and spend rest of my time in Finland learning as much as I could of it.

So I started to block out the Finnish and focus on the Swedish, but then I would pick up some written Finnish along with the Swedish and not realize until afterwards which language was it that I was reading. No, no, no, that was not how we planned it. Finnish was not what we were supposed to be able to read. (And strangely, I would then try to come up for the Swedish counterpart of the Finnish I just came by, and it wouldn’t come to me).

This year, regardless of whether I was at a good place in my Swedish, I decided to start Finnish. And I have never been as much afraid of sitting in a class in my whole life!

My fear was not unfounded. When we were supposed to come up with the Finnish for Saturday, my mind would scream “lördag!” (Saturday in Swedish), and seeing the number 4, it would be all “fyra, fyra, fyra, FYRA!” in my head. I don’t know if that is a good or bad sign, but I have so far been successful in not replying in Swedish to any of the questions.

But learning Finnish has also motivated me to ramp up my Swedish learning curve, because once I am surer of my Swedish, I wouldn’t mix it up with my Finnish. And while I knew objectively that they were two totally different languages before this, I now really know how totally different they are from each other (and how they sound so crazy sometimes when you look at them from each others’ perspectives: You are not supposed to change the sentence structure when forming questions in Finnish? Why would you do that?! How in the world can you have front and back vowels in the same words in Swedish? That doesn’t make sense!).

But we try and prevent all sorts of brain-scrambles. And I haven’t even started comparing Finnish to my other three languages.

Feels Like Friday

Friday is not just the name of a day of the week, it is the name of a feeling. And sometimes, the whole universe feels this feeling with you (as evidenced by nothing going right and equipment often not working on a very particular day of the week).

This week, every day had been feeling like a Friday for some strange reason, and then I realized that this week really was the “Friday” of the year.

No wonder I have been running high on introspection – typical “Friday” mood. Not to mention, this “Friday” also marks the official mid-point of my PhD, which means that the time is ideally situated to look back on how far I have come and how to best manage the rest half.

So, upon the (partially) successful survival of my two years in Finland and in my PhD, I sat down to count my little successes along the way, which took me perhaps five minutes, not much there. I’m also pretty sure that I’m still navigating the unpredictable waters of culture shock and adjustment, but now I find myself on stable ground more often than not (I would probably put together my final thoughts on the subject, which are still worth about three to four blog posts).

But there is light in the middle of this tunnel. Lately, I have finally been seeing some shape and form from my last two years of optimizations. Or that’s what I would like to believe (the human brain is really good at erasing information that causes it discomfort, so maybe I’m living in my little, custom-made, fantasy bubble).

Today, I did a little exercise. I made boxes for each week I was getting in the next two years (inspired in part by a part of this brilliant and funny TED Talk). Before this, I didn’t know how uncomfortable a task as simple as drawing and counting boxes, can be.

As of 29 December 2019, I have 105 boxes. Don’t look like all that much.

Really put things in perspective for me.

The Language Barrier

Some background information first: I am a foreigner in Finland.

It happens so, from time to time, that when people from my home country are considering a PhD abroad, particularly in Finland, and they somehow know me (directly or through mutual friends), we get into conversations about the pros and cons, the good and bad stuff, the easy and tough parts.

One of the FAQs include the language question.

In my two years here, I have not yet come up with a good short answer. Is there a language barrier in Finland? No, but yes there is. Or more like, yes, but apparently not.

I find this to be one of the weird things about my whole experience, and I never imagined that the “language barrier” would play out quite like this.

Back when I was on the other side, and I was gathering information on different aspects of adjustment, and asking people and disentangling information from the internet webs, I was told that English is fine! Almost everybody speaks English and there are no problems. They are, of course, right.

Ask me and I will tell you that of course you can survive and move about fine with just knowing English. Heck, I have myself done it for almost two years now. But I will also tell you that despite this, there is, in fact, a language barrier in Finland. And because of this, the existing language barrier is never acknowledged. I will also tell you to not take this too seriously and this is probably kind of fine-print information (not to mention, everyone has different experiences and what might feel like an ocean to me could be just a drop in the bucket for other people).

Now, I have come to realize that my methods of adjustments rely heavily on the language. In a new place, it helps to know your boundaries and how much you can dive in appropriately. And, being potentially awkward questions to ask directly, how does one get this kind of information otherwise? By observing one’s environment and noticing the interactions between already-established people in the “culture” (read: by overhearing conversations).

That ways you know if you should just keep it work-related, or if you could joke around a little bit and share light-hearted, other-workly information. And as you put together your own big picture, you see where you can and cannot fit in, in what aspects will you be limited yourself, and if you can establish a state of equilibrium with your environment.

In case there’s a “language barrier”, you are cut-off from this very important source of information. And in case of Finland, where, as the internet says, people don’t talk, or don’t like to talk, or whatever it is actually that they have with the act of talking, this effect is magnified.

So when they are talking among themselves, what is it really that they are talking about? Just work, probably? Or that’s how you start off, more or less.

Now, in my two years of observing and speculating and trying to put together the pieces of my yet-incomplete puzzle, I have reached the conclusion that the Finns do talk, at least, but they are probably not always talking about work. Though still not sure how much. Also not sure if they have a gossip culture and office politics. Also not sure how much is appropriate and how much isn’t. To some extent, I can tell which people in my environment are more friendly and which are not as friendly with each other, but I cannot say how much friendly those people are with each other.

So, yes, there’s a language barrier in Finland that nobody is ready to acknowledge because, of course, everybody speaks English, and what needs to be communicated is being communicated. Survival prospects of internationals are actually pretty nice, even if they are not up for learning the language.

Another way that this language barrier is amplified is when you are sitting in a group and the already-established people just kind of forget you are there and start conversing in their local language. The feelings of exclusion can be tremendous and these can be the main moments where you truly experience a “culture shock”. Still, I assume this is relative to what culture you are coming from and what your host culture is. I expect that in more social and inclusive host cultures, this might not hit a new person so hard (if they feel included in other aspects in their environment).

(Older posts on culture shock: here and here).

There’s only one way I have found around this, so far: Learning the language, irrespective of if you are good with communicating in English only, and even if you are not planning to speak in your new language. Having now taken two Swedish courses, I can tell at least when they are talking in Swedish vs. Finnish. Also, recently I realized that while I can still not understand what the already-established people say while talking among themselves, I can finally get the gist of what is being talked about.

Most importantly, if you are in a gathering and they forget you and start talking among themselves, it at least becomes interesting to try and understand what they are talking about, or you can just imagine it as your usual Swedish listening practice.

An Important Article

Sometimes, wandering in the field of research articles, you come across some outstanding work that leaves a mark on your mind for days to come. Just like this research article did. While the article itself speaks volumes, the good thing about this article is its universal language, that anyone from any background can easily follow.

And the best part is that a video of the research presentation by the author is available as well (although not of great quality, but what does it matter, as long as high-quality work is being communicated).

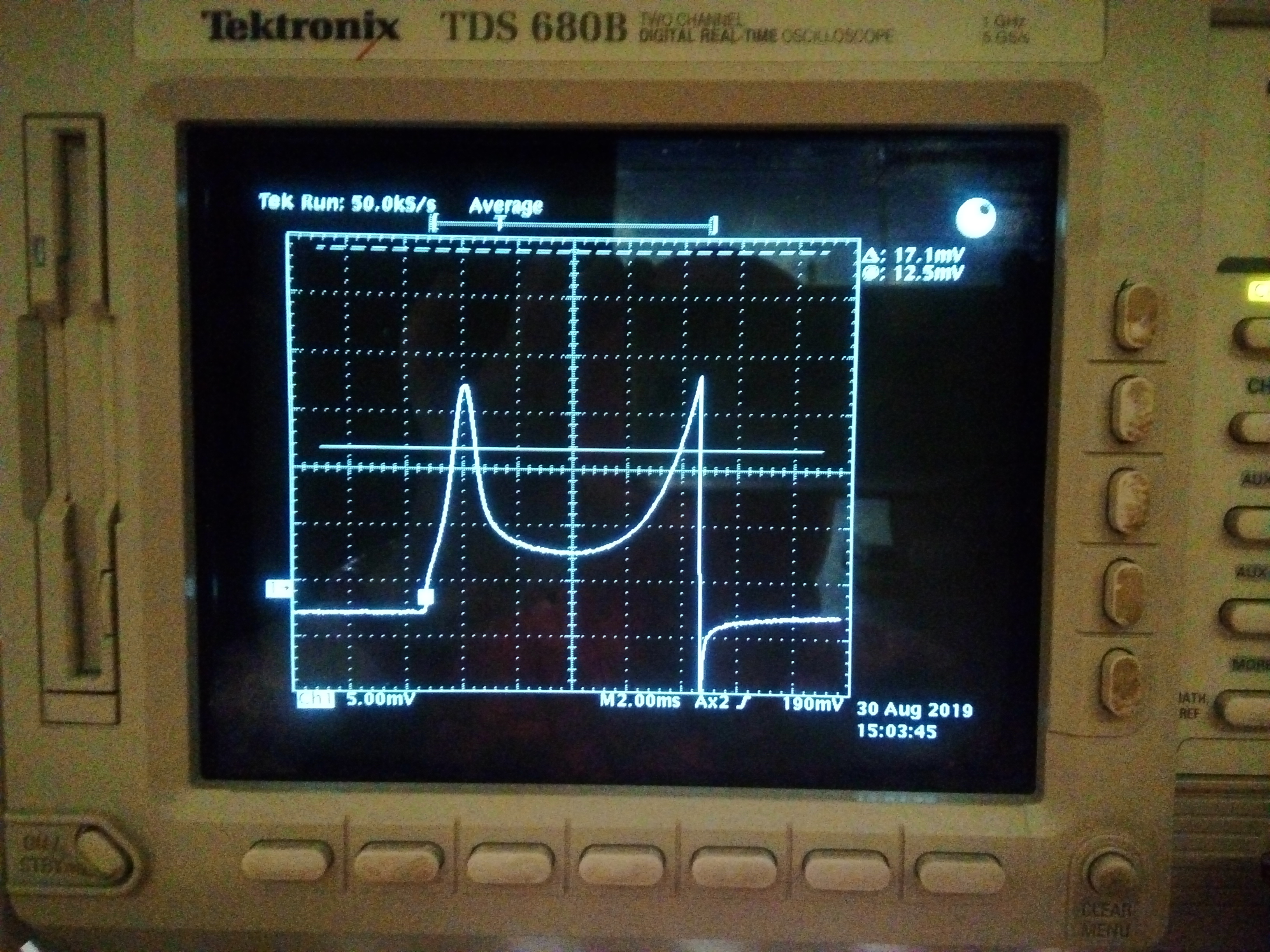

Bat Signal

A couple months ago, while measuring some samples with an oscilloscope, I witnessed a never-seen-before phenomenon.

As is completely obvious, the results were undoubtedly a part of some bigger picture.

Is this a signal from the universe? Some kind of a message?

Is that you, Batman?

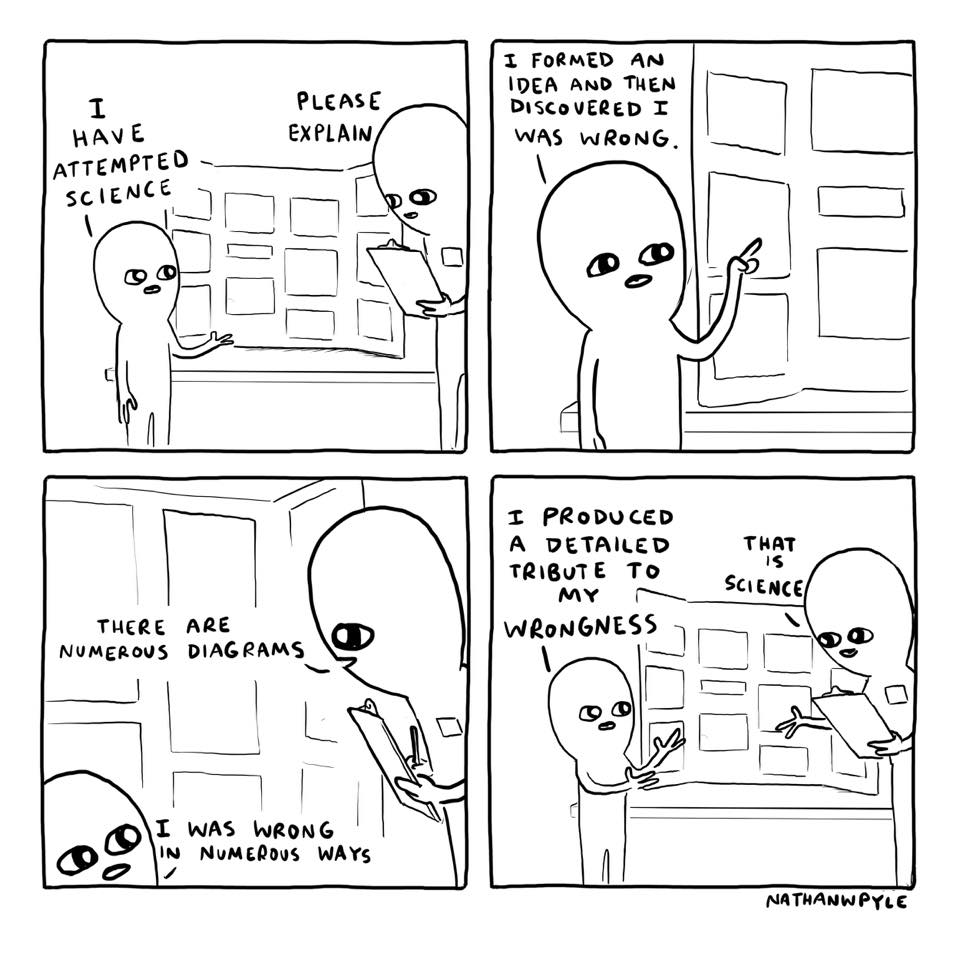

How To Science

So today, I came across this very inspirational post and decided to hold onto it. It was a good reminder that discovering you are wrong is still science (if attempted scientifically).

(Source).

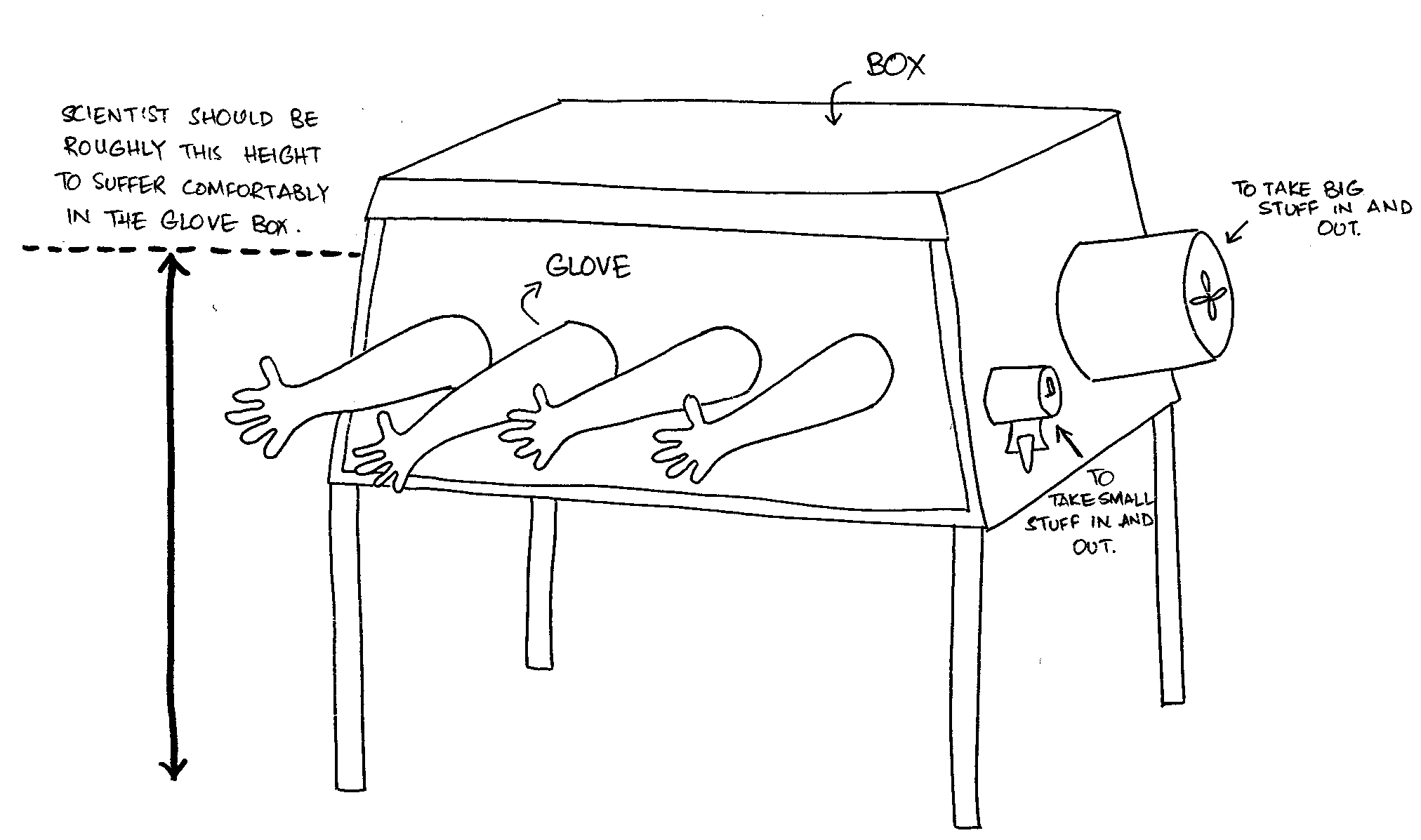

The Glove Box

Lately, I’ve been interfacing with the glove box a lot, which is next to inevitable in my field of study.

If you have never seen or heard of a glove box before, I have got an exclusive, self-explanatory diagram of it to show. But like all things science, this story is not as simple as that.

If your glove box is big, in a looming sort of way, it can be quite intimidating at first. And it can seem so… fancy to be working in a glove box then. Like you had to qualify for it. Well, with more experience, you find out that the basic qualifications you need are: 1) having a piece of work that you need to do in a glove box; and 2) appropriate height (as in, tallness of a scientist) relative to the glove box (but let’s be real here, the second criterion doesn’t really exist – stand on a chair if you must).

Plus, having to wear thick big gloves of the “glove” box, it becomes plain clumsy to work in it. And my excuse of “I-am-still-new-to-working-in-the-glove-box” expired a long time ago (which I actually whined about for quite some time compared to normal, not-so-fussy people).

So now I have had to accept that I AM fully responsible for whatever clumsiness I commit – which makes me not-such-a-big-fan of the bumbling person who works in the glove box and cannot even pick up a bottle without first dropping it a couple of times.

The “person” who works in the glove box? Pfft! That’s not me! She is Qudsia Forcephands (secret note: that’s the name for my alter ego for when I have to work in the glove box). She had to be really pushed to start working in there and she kept complaining about how she was still new to working in the glove box even when it was her sixth time! (it’s UNBELIEVABLE what some people will say so they will not have to work, it’s really sad).

But I think, with time (and with MUCH encouragement and suggestions from me), Forcephands is learning the tricks of the trade and she has become waaay better at navigating inside the glove box now. And, as the name might give you an idea, she is now quite adept at using forceps almost as if they were extensions of her hands (or gloves of the glove box).

Forcephands is still somewhat lazy and I often have to give her pep-talks, and even now, she keeps dropping everything in the glove box (are all those forceps inside the glove box there for nothing? Tut tut). But what can you do, some people will just remain at their level no matter how much you try. She has, though, become quite independent at working in the glove box now and, I have to admit, I am somewhat proud of her.

(But I still don’t completely trust her).

Stupid Questions

They say that there are no stupid questions.

And yet, in classrooms, presentations, and seminars, it’s very typical for to-be questioners to start with “maybe it is a very stupid question, but…”.

Often, once the question is out there to be judged for its “stupidity”, you find out that it was not a stupid question at all. That could be because there really are no stupid questions (or are there? We have probably not phrased every possible question in every language to make this assumption, so let’s just say that most questions are not stupid).

And yet, even though there are probably no stupid questions, we still like to call some questions stupid (or would have others and ourselves believe that). Working in science, where it can be very important to have the correct terminology, I sometimes wonder if it is really the right thing to do.

In my short career as a scientist, I have also come to believe that it’s rare when a question is stupid (probably only the ones that flit through my head). The thing is, we have been judging the quality of questions on wrong parameters. When you are all these scientists, where everyone is quite competent at what they do themselves, and not-so-good at what the others do, and no two people are working on the exact same thing at the same time – it becomes tricky. While some questions can be quite basic for some people, they can be a whole novel perspective from another’s point of view.

So, in reality, there are no stupid questions; only rookie questions, basic ones, newbie’s perspectives, outsider’s outlooks. These are all far, far from stupid.

All “stupid” questions just need to be relabelled.

P.S. The author has nothing personal against the word “stupid”. All views expressed in the post are completely neutral and unbiased.

Discoveries in the Lab

So it happened some days ago, during an unusually in-depth cleaning session of the lab, that we came across super-strong magnets. Such a great discovery should not be in vain. So since then, we have been trying to come up with some uses for these.

I mean, they can be very useful to pull magnetic stirrers out of a solution if you don’t want to throw away the solution or contaminate it by putting something else in it. But THEN, the magnets might be so strong that if you would use a pair of “metal” forceps to grab the magnetic stirrer sitting on the lip of the bottle, the super-strong magnets might deflect the FORCEPS themselves and you may not be able to grab the magnet AT ALL (yes, I tried – in a casual evasion-of-common-sense moment).

But of course, that could not be the only possible use. What if, instead of pulling the stirrers out of solutions, you wanted to keep the stirrers INSIDE? Like when you are washing magnetic stirrers in a bottle and you come to the part when you have to drain the liquid (soap solution, ethanol, etc.). There’s always a risk of dropping the stirrer with it, which means you have to wash it all over again (depending on where you actually drop it).

So then, if you would use a super-strong magnet (or maybe even just a magnet), you can keep the magnet inside while completely inverting your bottle to drain the solvent. Can be pretty useful sometimes. And now you have a use for super-strong magnets lying around (or rather, sticking around) in your lab.

And as I am now discovering, they are also quite good for designing little games. Like taking smaller magnets and dropping them close enough to the bigger magnets and see how they deflect the dropping magnets. If you control the distance precisely, you can make them hit a particular point on a metal pole.

And there, now you have a game of magnet darts (and another use for super-strong magnets lying around in your lab).