Okay, you don’t have to do much; write one sentence and we’ll consider it a win.

Trylingualism

So you are in this foreign country now. And you have been learning a new language for some time.

One day, in the streets, you pass some street sign and, woah, you could understand (some of) it!

After some time, it becomes quite common – that you look at some written words and you totally understand what they mean. Piece of cake, so easy. So easy that you don’t even notice it anymore.

On another particular day, you pass a sign and you understand it, as usual. But THEN, you realize that that sign was NOT in the language you were learning. You were not supposed to understand this one. Oh no!

This was the big question about learning a language in Finland. The main language is, of course, Finnish. But then Finland has a Swedish-speaking minority and the university that I was going to was the Swedish-Speaking University of Finland. So which one to learn? Swedish or Finnish? (Well, the answer to that was: Both!). Or rather, which one to learn first? Finnish or Swedish?

Back when I was coming to Finland, I had already started doing Finnish vocabulary, but once here, I decided to opt for Swedish. Swedish was easier to learn (so said the internet) and I could see an end point for it. Not to mention, the people in my more immediate surroundings were Swedish-speakers.

So this is how the equation set in my mind at that time: If I would start Finnish and it would take me two years, I might still not be good enough, making it unfavorable to start Swedish. But if I start Swedish, which was easier to do, there was a bigger possibility that I might reach a stage where I could then jump to Finnish, and spend rest of my time in Finland learning as much as I could of it.

So I started to block out the Finnish and focus on the Swedish, but then I would pick up some written Finnish along with the Swedish and not realize until afterwards which language was it that I was reading. No, no, no, that was not how we planned it. Finnish was not what we were supposed to be able to read. (And strangely, I would then try to come up for the Swedish counterpart of the Finnish I just came by, and it wouldn’t come to me).

This year, regardless of whether I was at a good place in my Swedish, I decided to start Finnish. And I have never been as much afraid of sitting in a class in my whole life!

My fear was not unfounded. When we were supposed to come up with the Finnish for Saturday, my mind would scream “lördag!” (Saturday in Swedish), and seeing the number 4, it would be all “fyra, fyra, fyra, FYRA!” in my head. I don’t know if that is a good or bad sign, but I have so far been successful in not replying in Swedish to any of the questions.

But learning Finnish has also motivated me to ramp up my Swedish learning curve, because once I am surer of my Swedish, I wouldn’t mix it up with my Finnish. And while I knew objectively that they were two totally different languages before this, I now really know how totally different they are from each other (and how they sound so crazy sometimes when you look at them from each others’ perspectives: You are not supposed to change the sentence structure when forming questions in Finnish? Why would you do that?! How in the world can you have front and back vowels in the same words in Swedish? That doesn’t make sense!).

But we try and prevent all sorts of brain-scrambles. And I haven’t even started comparing Finnish to my other three languages.

The Language Barrier

Some background information first: I am a foreigner in Finland.

It happens so, from time to time, that when people from my home country are considering a PhD abroad, particularly in Finland, and they somehow know me (directly or through mutual friends), we get into conversations about the pros and cons, the good and bad stuff, the easy and tough parts.

One of the FAQs include the language question.

In my two years here, I have not yet come up with a good short answer. Is there a language barrier in Finland? No, but yes there is. Or more like, yes, but apparently not.

I find this to be one of the weird things about my whole experience, and I never imagined that the “language barrier” would play out quite like this.

Back when I was on the other side, and I was gathering information on different aspects of adjustment, and asking people and disentangling information from the internet webs, I was told that English is fine! Almost everybody speaks English and there are no problems. They are, of course, right.

Ask me and I will tell you that of course you can survive and move about fine with just knowing English. Heck, I have myself done it for almost two years now. But I will also tell you that despite this, there is, in fact, a language barrier in Finland. And because of this, the existing language barrier is never acknowledged. I will also tell you to not take this too seriously and this is probably kind of fine-print information (not to mention, everyone has different experiences and what might feel like an ocean to me could be just a drop in the bucket for other people).

Now, I have come to realize that my methods of adjustments rely heavily on the language. In a new place, it helps to know your boundaries and how much you can dive in appropriately. And, being potentially awkward questions to ask directly, how does one get this kind of information otherwise? By observing one’s environment and noticing the interactions between already-established people in the “culture” (read: by overhearing conversations).

That ways you know if you should just keep it work-related, or if you could joke around a little bit and share light-hearted, other-workly information. And as you put together your own big picture, you see where you can and cannot fit in, in what aspects will you be limited yourself, and if you can establish a state of equilibrium with your environment.

In case there’s a “language barrier”, you are cut-off from this very important source of information. And in case of Finland, where, as the internet says, people don’t talk, or don’t like to talk, or whatever it is actually that they have with the act of talking, this effect is magnified.

So when they are talking among themselves, what is it really that they are talking about? Just work, probably? Or that’s how you start off, more or less.

Now, in my two years of observing and speculating and trying to put together the pieces of my yet-incomplete puzzle, I have reached the conclusion that the Finns do talk, at least, but they are probably not always talking about work. Though still not sure how much. Also not sure if they have a gossip culture and office politics. Also not sure how much is appropriate and how much isn’t. To some extent, I can tell which people in my environment are more friendly and which are not as friendly with each other, but I cannot say how much friendly those people are with each other.

So, yes, there’s a language barrier in Finland that nobody is ready to acknowledge because, of course, everybody speaks English, and what needs to be communicated is being communicated. Survival prospects of internationals are actually pretty nice, even if they are not up for learning the language.

Another way that this language barrier is amplified is when you are sitting in a group and the already-established people just kind of forget you are there and start conversing in their local language. The feelings of exclusion can be tremendous and these can be the main moments where you truly experience a “culture shock”. Still, I assume this is relative to what culture you are coming from and what your host culture is. I expect that in more social and inclusive host cultures, this might not hit a new person so hard (if they feel included in other aspects in their environment).

(Older posts on culture shock: here and here).

There’s only one way I have found around this, so far: Learning the language, irrespective of if you are good with communicating in English only, and even if you are not planning to speak in your new language. Having now taken two Swedish courses, I can tell at least when they are talking in Swedish vs. Finnish. Also, recently I realized that while I can still not understand what the already-established people say while talking among themselves, I can finally get the gist of what is being talked about.

Most importantly, if you are in a gathering and they forget you and start talking among themselves, it at least becomes interesting to try and understand what they are talking about, or you can just imagine it as your usual Swedish listening practice.

The Finnish Happiness

When you are a foreigner exploring a new culture, there is no shortage of stuff to wonder about. Something will keep coming your way throughout your stay.

And so it has been many times when I (and my fellow foreigners) have wondered about Finland being the happiest country in the world, time and again.

This journey of discovery is to each their own. You can search it on the internet and easily find articles analyzing what the reasons are for it. But when you are living in Finland, that is just not enough, is it? You will notice your surroundings, think about this, discuss it with others, and try to find out why in the world is it so (because those articles on the internet, what do they know about it).

And in my personal journey-of-discovery, I think I may have come upon at least one profound, contributing factor.

Finland is basically a happy country. By default. In other parts of the world, people become happy if something happens, but in Finland, you can be happy if something doesn’t happen. Like slipping and falling on ice. This has to be one of the biggest factors. Like you went to work, walked the full some-150-meters distance of it, didn’t slip and fall down, and now you can be happy about it. In fact, now you can be happy about it everyday (seeing as the ice doesn’t seem to be going anywhere any time soon).

Tasks as mundane as getting groceries suddenly become feats of accomplishment (because, you guessed it, you didn’t slip and fall during the entire time you were out). And of course, this also gives rise to a sense of camaraderie with your fellow pedestrians, especially if you see someone slip a little and stumble. Then you can root for them to please-not-fall (and be happy for them when they have regained their balance).

Looking at it statistically, it is far more likely that you will have more days when you wouldn’t slip and fall compared to the few days when you, inevitably, will do. So more happy days. At least in this time of the year.

And if you can be happy in this slushy, icy time of the year, that should probably count.

Culture Shock (Again)

Wait, haven’t I written about this before?

Seems like I have… But l appear to have the phrase stuck in my head.

Never mind, I’m a changed person now, so anything I write today (on the same topic) cannot be the same as what I might have written four (and something) moons ago.

So I shall write on this again.

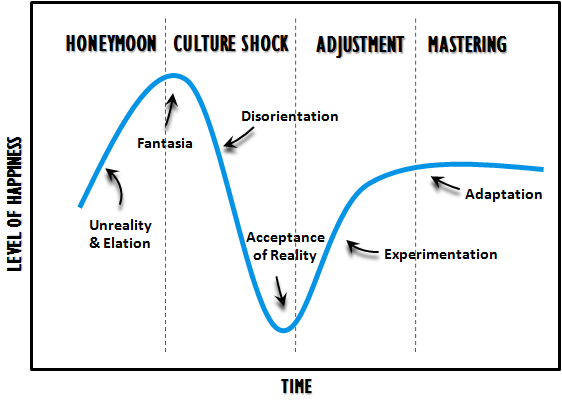

And today, now eight (and something) moons into my PhD, I expect myself to have grown somewhat in my scientific capabilities. So we shall talk about culture shock the scientific way, the “graph” way (excuse my English, but I am a foreigner, so I can apparently do whatever I feel like without feeling as bad about it).

And well, the graph-way is the right way, or it becomes so once you start falling in love with this kind of data representation, which is inevitable if you science (again, I am a foreigner, and “science” feels more like a verb to me these days).

But anyway, back to the graph:

Of course this is a very generalized curve, and just one “dip” in the experience is untrue for quite some people – this graph should be a lot more “noisy” if you’d plot a real one. Although this would differ from person to person, and how different of a culture you are moving into.

Also, the graph doesn’t really show your “mastery” level at your home country (or town). But from the text available on the internet, it is apparent that you almost never reach the same level of mastery in your new culture that you had in your old culture (which makes sense if you think about it).

This always makes me wonder… Does this mean that, even after you have adjusted and adapted, you are technically still in a state of culture shock, and will probably remain there throughout your stay?

That I find scary. And a little unrealistic to mention if a discussion about culture shock comes up in, say, two years from today. What do I do then? Do I say I am still in culture shock, if this particular question comes up? (Although I would estimate that to be a highly unlikely scenario, but everything has a first time, doesn’t it?)

But having grown comfortable with the idea of culture shock, and the (somewhat embarrassing) fact that I am still in there somewhere (although now probably in an overall better part of the curve), and being there for perhaps as long as I am in Finland, I have also realized the good this will do to my self-esteem…

So if I am not as good as I am hoping to become… heck, I am just in the wrong country!

Other Stuff

A while back, I came across this post about how science can make you feel stupid.

I shared it, thinking I understood perfectly what it meant and felt like. I actually didn’t then, because now I know what it means and feels like. (And yet, I am not exactly sure how it feels like. Stupid can take so many forms).

When I started off my PhD, I was like any normal person, motivated about starting a new “project” that they are excited about. It’s just like new year, and we all know how that goes:

1) You start off with a long list of resolutions;

2) You start following through on almost all of them immediately;

3) You feel so good that you are following through, and how this year did not turn out like last year (and we all know how that went);

4) You start realizing how by starting everything, you broke all rules of developing new habits, and how this is not sustainable at all (did you really even want all of this?);

5) You start going back to your normal routine, and your resolutions start feeling less important to you now;

6) New year, and you have almost forgotten (almost) how last year went and are ready for a new cycle of highly-motivated-to-back-to-“normal”.

But of course, everybody knows these stages, everyone has new-year moments. And when I started my PhD, I knew I’d face some kind of a slump some of the times. People-on-the-internet told me that the PhD dip is inevitable, and it is not a question of if you will come across it but when you will actually experience it (although they also told me that this phase comes sometime around the second year and I am still in my first, so am I just going through a trailer for the actual movie that will be officially opening in months to come?).

The thing is, despite knowing this, I didn’t really plan for this time (that is another kind of stupid right there). Because, like any normal person motivated about starting a new “project” that they are excited about, I wanted to be laser-focused on my PhD and on things that would take it forward.

So if I needed a break from lab work, I could read or catch up on literature, and if I needed a break from reading, I could take some online course. I did like doing other stuff, but all of that could wait until I had my PhD a little more on routine (a thing, that I am finding out only now, was not as easy as I supposed it was, but that could be for another time).

And this is the importance of comparatively-dumber-sounding other stuff.

Because when you are doing something as crazy as a PhD, where you can go months running around in circles finding your way back to square-one’s, feeling-stupid does become inevitable. And when you see it’s been a while since you last made progress, or learnt something new, or developed a new skill, or added something to you, yourself, as a person, that can be eexxttrreemmeellyy demotivating.

But other stuff can help you here.

Because if you have a little something going on the side, like learning a new skill that may not be completely related to your PhD, it is some progress that you can, at least, show to yourself: So, yes, I still haven’t been able to decide if zinc chloride is better or if I should go for zinc acetate for my solutions, but I have completed six-hundred-and-eighty-five blog posts! That should be a milestone!

So that’s why I have started to think about starting other stuff this new semester. Like taking a language course (I have always wanted to learn another language and now might be a perfect opportunity), or starting to draw (I have some half-developed scripts for a comic on how my PhD stuff is going), or taking up other random workshops and activities where I can just change my environment and see what else is up in the world.

And there is another reason why the other stuff can be so complementary to your PhD: so now when you are moving about progress-less, you can blame it on the other stuff, and how, because of other stuff, you probably have not been able to focus on your PhD.

But the other stuff was your stupid idea, wasn’t it?

Fast Lessons

So for the last month, I have not been blogging much.

I’m a Muslim, and we recently ended our month of fasting, in which we don’t eat or drink from pre-dawn to a little after sunset. In Finland, particularly in Åbo, that makes about 20 hours. So while we are fasting, we often switch to this energy saving mode to get through the day with grace, while not completely going into some kind of hibernation mode (which we (most of us) do go into if we are on vacation).

So, for reasons mentioned above, I was not much into anything apart from food thoughts and how-to-get-through-the-day-while-keeping-some-lab-work-going techniques (and managing my sleep deprivation issues).

But all this down-time also helps you reflect on what you are doing, and why you are doing it, anywhere from life in general to specific PhD related stuff. And this year, Ramadan (that’s what the fasting month is called) taught me something that I think I’ll be needing much reminding of in the four years of my PhD:

That you think you cannot do it, but you can.

Whenever this thing came up about me (or us Muslims) not eating or drinking anything for 20 hours straight, people would mention how they cannot go through without food and water for this long. Even we, Muslims, who get this training repeatedly every year for 30 days, cannot think of going without food and water for this long when we are not fasting.

But when we are fasting, we do.

And this is quite strange for me, because now that Ramadan is coming in summers*, we always have this big worry on our minds about how we will get through it this time, specially without water (I, in particular, whine a lot about this one). It sometimes seems so hard, and at times, so impossible.

And yet, when we start fasting, we do. Every time. The whole month.

And this year, I realized, how we are always making assumptions and excuses about how we cannot do something, without really trying it out. We don’t take into account the fact that the human mind and body are very flexible and adaptable, and we become what we make out of ourselves.

In my PhD, I know that I’ll come across multiple instances when I’ll think I cannot do this anymore, or how I am not able to try any further with a particular experiment, or when taking the next step forward will seem like the most difficult thing to do.

But all that will just be stuff in my head unless I try and find out that I was able to do that all along (or not).

And that, when the start is difficult, it only becomes easier as you move forward.

—

* Ramadan shifts by 10 days every year because we follow a Lunar calendar for this, which is 355 days long compared to the more-common 365-day solar calendar.

Culture Shock

So, I am back from my weekend and my latest episode of culture shock.

When I was coming to Finland, I hadn’t taken the culture shock phenomenon very seriously (unfortunately, it wasn’t so the other way around). I mean, I already was aware that there’d be cultural differences, and that (duh) I’d had to adapt. Nobody said it is going to be easy but how hard can it get, still? I had been reading up on life in Finland, so I was mentally prepared and pretty excited to move here and experience it.

And that, dear reader, is what you call the gap between theory and practice.

I vividly remember when I first discovered I was in a state of culture shock: It was a moment of disbelief and enlightenment (if you can call it that). In fact, for this first time, I covered the distance between being-miserable to being-awestruck within 5 minutes (once I realized I was actually going through culture shock – I’d never really thought it was real).

I have found that with things like culture shock, it is very important to know what you are going through. This fact arms you with a very useful piece of information, and if you’d like to think of yourself as an experimental subject – a guinea pig in a lab, a hamster in a cage – it can turn your experience extremely entertaining (in retrospect, of course. It is quite stupid how the smallest of things can sometimes send you off into one).

They say there are four stages of culture shock:

The first one is your very excited, super-smooth, what-culture-shock-excuse-me stage. Everything is so… normal. After all, we are all people, and people, more or less, work the same way, right? You have unlocked the secret of adapting anywhere, this is just so simple.

The next one is the actual culture shock, I-don’t-know-what-I-was-thinking-(with-an-exclamation-mark) phase. This is when you suddenly realize that the place and the culture you live in now has a new normal, which is not at all what you have been thinking of “normal” all your life. Which makes you revisit all the other definitions that you had so far assumed about life. Which makes you realize that you weren’t on the same page when they said culture differences on the internet. Which is now the beginning of your culture shock, congratulations for making it this far.

After this, there should be two more stages to go, but I wouldn’t know about those – haven’t reached there yet. They should come when after repeated iterations, you have successfully reset your data to accommodate all alternative protocols that you will now need to survive in this new culture.

If you ever come across this state of mind, and are able to see it for what it truly is, your first instinct might be to close up and draw back. That is the easiest and the instinctive thing to do about it: to let it blow over.

Only, it won’t – this is a recipe for more-culture-shock. Because eventually, you will need to make contact, whether in two months or two years. So you have two options: close up or get it over with. Though this can become a problem when you don’t know how to make contact (culture shock might take away some of your social abilities and/or creative powers to deal with culture shock).

The situation will likely yo-yo for some time. So when you are in the shock phase, it helps to take into account why you had overestimated your cultural understanding and overall sensitivity to your new environment: in simple words, you had probably been expecting something that didn’t turn out quite the way you thought it would.

But then, one day, you’ll wake up and find out, heyy! no culture shock anymore! Beware, this is a lie. Never assume it is over, the sneaky little thing is probably just hiding behind your curtain. But this peek-a-boo phase is perfect for pushing yourself a little more into the culture, forming a support network, and finding out activities that you can do around.

And then there are a lot of other tiny things that can help, like blogging about it, talking to a trusted friend, taking up sports or hobbies.

They say there’s this thing then called reverse culture shock. I thought it was a figment of someone’s imagination but now I think I am changing my mind about it.

The Finnish Winters

This seems to be the primary ice breaker in Finland: “So, how are you enjoying the Finnish winters?” (It’s even phrased almost the same way). Or may be that was just because I arrived here smack dab in the middle of winters.

Sometimes I laugh it off. Sometimes I just do a general commentary on that day’s weather. And sometimes, I admit to hating it.

Where I come from, it’s 48-degree-Celsius-in-peak-time-of-summer hot. And snow, that’s fairy dust for us. People revere snow. Of course, we do have snow in some parts of the country, and all trips to these “exotic” regions are planned according to when there’s snow in the forecast or the news.

Apart from these once-in-a-while excursions, we are not adapted to winters that are as frigidly cold as the Finnish ones, or as dark.

Here, there’s more snow in a month than the total I had seen in my life before coming here, so of course after a while, I started suffering from this condition called too-much-snow. But then the days got longer and we moved from snow to slush, and it was all going very well. In fact, it was happening just like I expected it to – except that it snowed in again after some days, and again after some more days, and again.

So may be it was my pride that got hurt (because it didn’t go just as I expected), or my elbow when I slipped on a bad piece of ice, but I cannot say I will have fond memories of my first Finnish winter (which, people tell me was colder in this part of the country than it usually is). May be next year, when I’m more adapted to the cold, and have probably gotten myself into trying something winter-specific.

It’s all good for some time, but man! where is that spring season one of my colleagues promised me was just around the corner?

The Finnish Doctorate

In the 3 months that I have been involved in a PhD at Åbo Akademi University, I have come to the conclusion that just the act of pursuing a PhD in Finland warrants keeping a blog about it.

Because Finland is right on the opposite end of the spectrum of all cultures I have experienced so far. This inevitably also shows up in how one organization, or one group, does research. I find it quite interesting how these “cultural” differences can dictate how you approach a scientific problem, and how you interact with the system and people around you.

This can make for topics interesting enough to make it worth it to drop the research process once in a while to document the experiences.

But then again, the PhD process itself can be full of ups and downs, and well, blogging is the obvious way to go about it for me.

So here’s to doctoring through a Finnish PhD, and writing about it.