Lately, I’ve been interfacing with the glove box a lot, which is next to inevitable in my field of study.

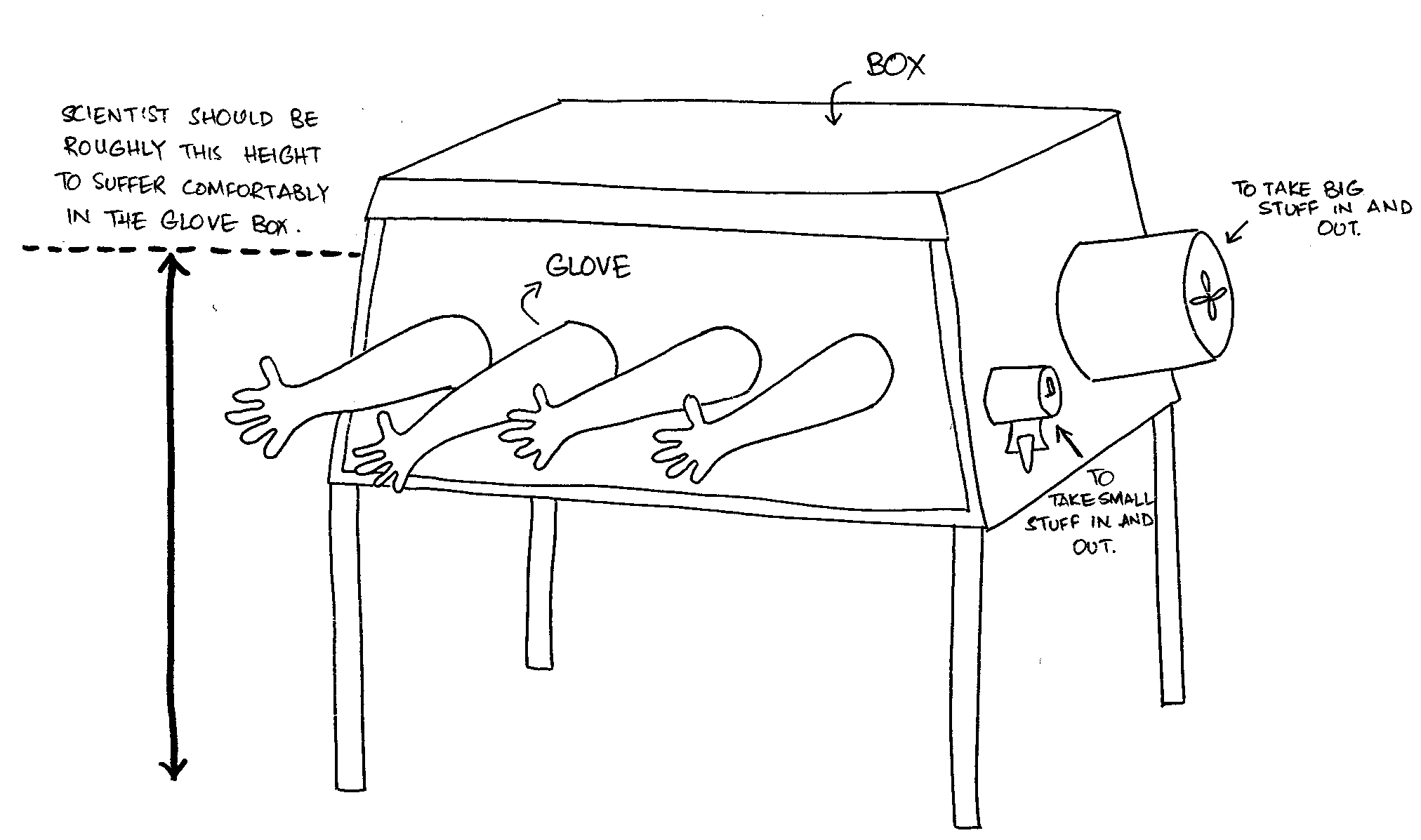

If you have never seen or heard of a glove box before, I have got an exclusive, self-explanatory diagram of it to show. But like all things science, this story is not as simple as that.

If your glove box is big, in a looming sort of way, it can be quite intimidating at first. And it can seem so… fancy to be working in a glove box then. Like you had to qualify for it. Well, with more experience, you find out that the basic qualifications you need are: 1) having a piece of work that you need to do in a glove box; and 2) appropriate height (as in, tallness of a scientist) relative to the glove box (but let’s be real here, the second criterion doesn’t really exist – stand on a chair if you must).

Plus, having to wear thick big gloves of the “glove” box, it becomes plain clumsy to work in it. And my excuse of “I-am-still-new-to-working-in-the-glove-box” expired a long time ago (which I actually whined about for quite some time compared to normal, not-so-fussy people).

So now I have had to accept that I AM fully responsible for whatever clumsiness I commit – which makes me not-such-a-big-fan of the bumbling person who works in the glove box and cannot even pick up a bottle without first dropping it a couple of times.

The “person” who works in the glove box? Pfft! That’s not me! She is Qudsia Forcephands (secret note: that’s the name for my alter ego for when I have to work in the glove box). She had to be really pushed to start working in there and she kept complaining about how she was still new to working in the glove box even when it was her sixth time! (it’s UNBELIEVABLE what some people will say so they will not have to work, it’s really sad).

But I think, with time (and with MUCH encouragement and suggestions from me), Forcephands is learning the tricks of the trade and she has become waaay better at navigating inside the glove box now. And, as the name might give you an idea, she is now quite adept at using forceps almost as if they were extensions of her hands (or gloves of the glove box).

Forcephands is still somewhat lazy and I often have to give her pep-talks, and even now, she keeps dropping everything in the glove box (are all those forceps inside the glove box there for nothing? Tut tut). But what can you do, some people will just remain at their level no matter how much you try. She has, though, become quite independent at working in the glove box now and, I have to admit, I am somewhat proud of her.

(But I still don’t completely trust her).