I recently attended a PhD seminar of a student at the Physics department. One interesting question that came up was: What didn’t make it to your thesis?

After deep thought and much analysis, I have realized this is such a good question. It let the candidate show other things he did and learnt in his PhD that didn’t make it to his thesis, because they may have been slightly irrelevant or might have been disregarded as not-important-enough.

But with this question, he could highlight this stuff because he still did those during his PhD (or more likely, he could highlight this stuff well if he’d been prepared for such a question to come up – this may not be your average kind of opponent-speak).

But hang on, is it just this stuff that doesn’t make it to your thesis?

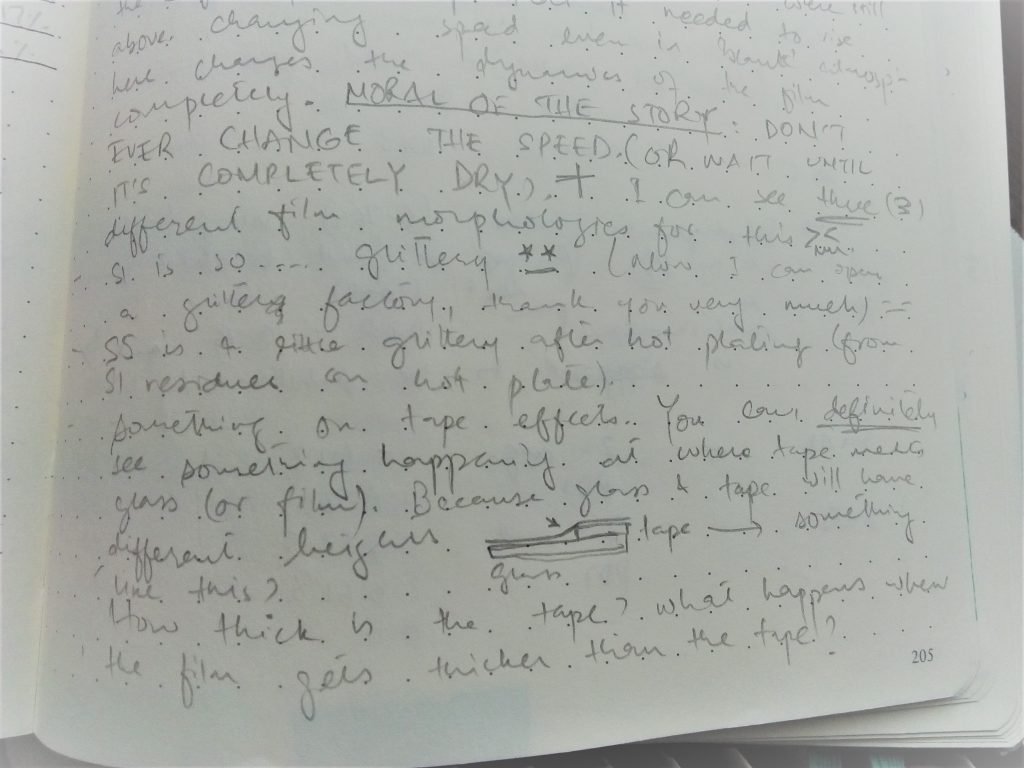

When I was doing my Masters, we’d always joke about how everybody should write 2 theses: One the more formal, “required” document; the other, a document of “failures”: the questions that we asked, and what we tried in the lab, that then didn’t work out, and that we then dropped… which then obviously wouldn’t make it to the thesis. The kind of information that you jot down in the side margins of your lab notebook, along with angry and frustrated emoticons and hashtags and exclamation marks.

The kind of information that doesn’t make it anywhere.

Because that information is also useful, although it mostly just tells you what NOT to do (which is quite the time-saving information). But this kind of information doesn’t have much space in the scientific world. Like people in all other fields, we just want to make noise about the best work that we do, disregarding the important stepping stones that our failures were that got us there.

So yeah, a lot of stuff doesn’t make it to the thesis at any level (or any important document, for that matter – except may be some internal lab communication).

There’s also a lot of other stuff that doesn’t make it to the thesis: the hardwork and energy that you put in, how you picked yourself up after repeated failures, how your informal collaborations helped you (and the people around you)…

… Although if you end up doing really good work, the thesis can become a reflection of it.